The festive season is always a stir-up of activity, over-the-top Christmas decorations, upcountry travels, lots of foods, and Boney M on repeat, the ultimate Kenyan Christmas tradition. But as data shows, price increases seem to be a steady part of the tradition too.

Despite the early predictions that the rising cost of living would improve as the country pulled out of the nationwide curfew and ramped up vaccinations, but as it appears, this Christmas is more expensive.

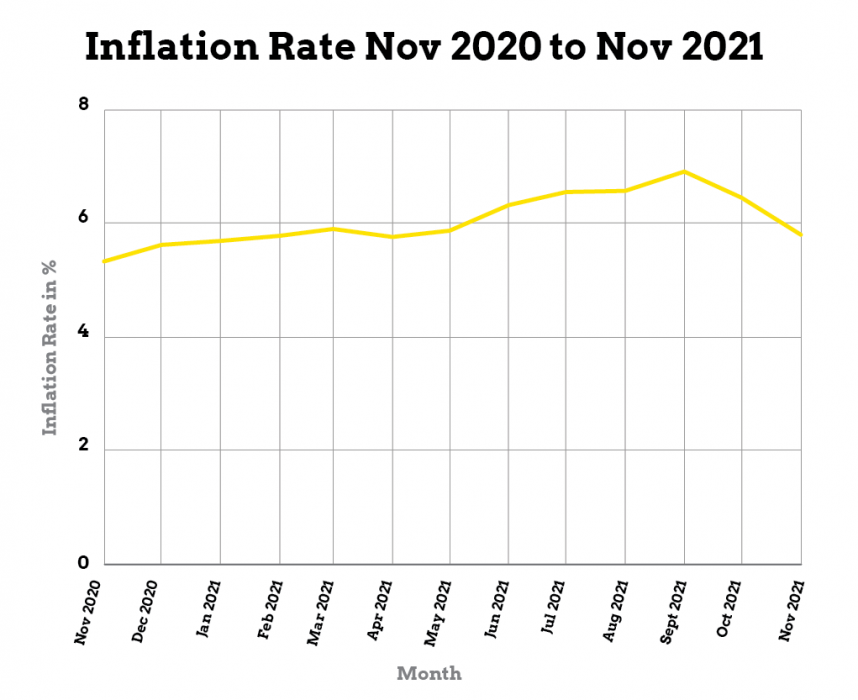

According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics’ Consumer Price Indices and Inflation report, the annual inflation rate fell marginally for the second straight month to stand at 5.80% in November of 2021, down from 6.45 percent in October. However, compared to November 2020, when the inflation rate was 5.33%, this is a surge. From the economic survey 2021, released in September, the retail prices of consumer goods have been on an upward trajectory since 2016, with only tiny marginal drops on select items.

While many Kenyans may not understand every nuance of inflation or how it relates to price increase or decrease, many acknowledge the pain of rising prices on their budgets, especially food prices. According to Kwame Owino, the chief executive officer of the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA-Kenya), Kenyans spend about 45% of their income on food.

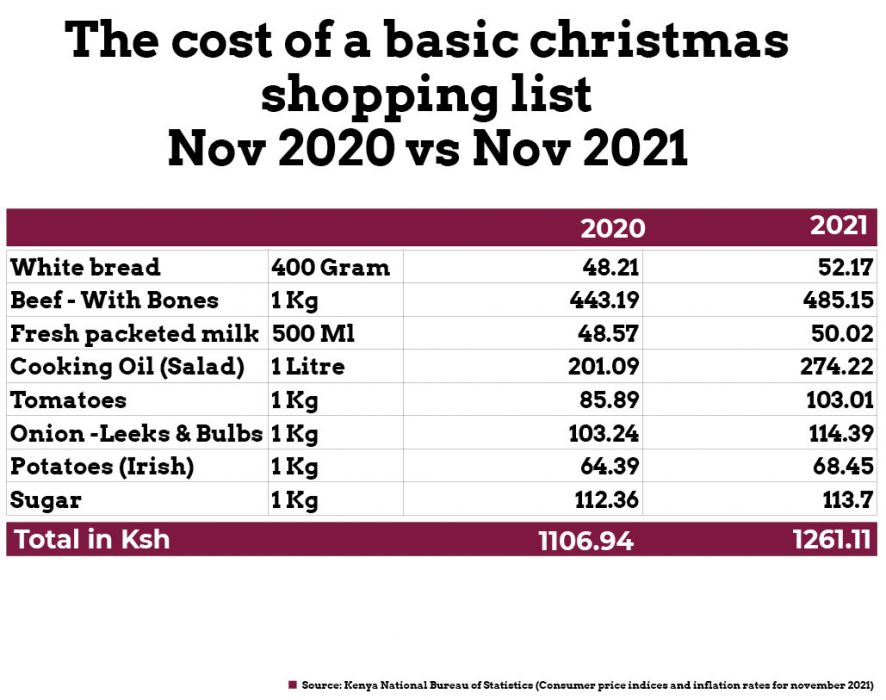

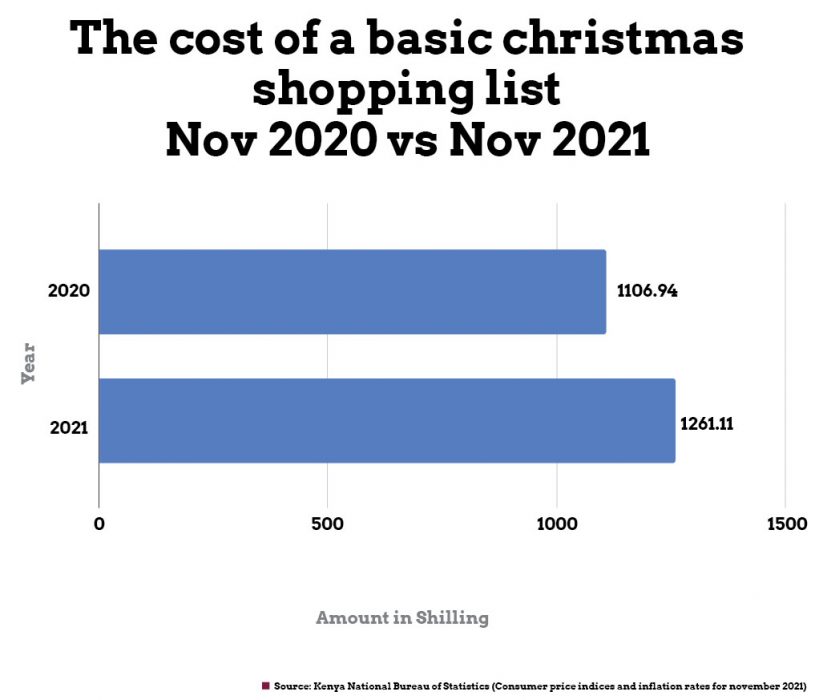

So just how much more are this year’s festivities going to cost you? If you were to shop for milk, meat, bread, maize flour, sugar, cooking oil, potatoes, tomatoes, and onions today, the total would be Ksh 1261, Ksh 154 more than in 2020.

The difference may not seem as much at face value, but as a percentage, 12.22 percent increase from 2020, the price changes are quite significant. For lower-income households, who have already endured the pandemic’s hardest pinch, this is hard-hitting.

The high food price in the year 2021 can be attributed to a mix of forces such as high cost of fuel, disruptions in the supply chain, depreciation of the shilling against the dollar, global food prices, end of economic relief from economic relief the government and unfavourable weather. In 2020, the agriculture sector benefited from favourable weather conditions that prevailed for the better part of the year, which helped stabilize the food supply.

In 2021, a global rally in wheat prices, for example, pushed up the cost of bakers and standard flour; this prompted an increase in the cost of bread and pastries. Wheat is Kenya’s second most important cereal after corn, and Kenya imports about 75% of the wheat consumed locally, with most imports coming from Argentina, the US, Ukraine, and Russia. Russia imposed a 50 euro (KES 6360) export duty per tonne of export wheat to discourage exports leading to costly imports for most wheat. Furthermore, Kenya being a net importer is affected by the performance of the Kenyan shilling against the US Dollar in the foreign exchange market. The dollar is the preferred currency of trade globally, and the continued depreciation in the shilling means that Kenya has to pay more for imports.

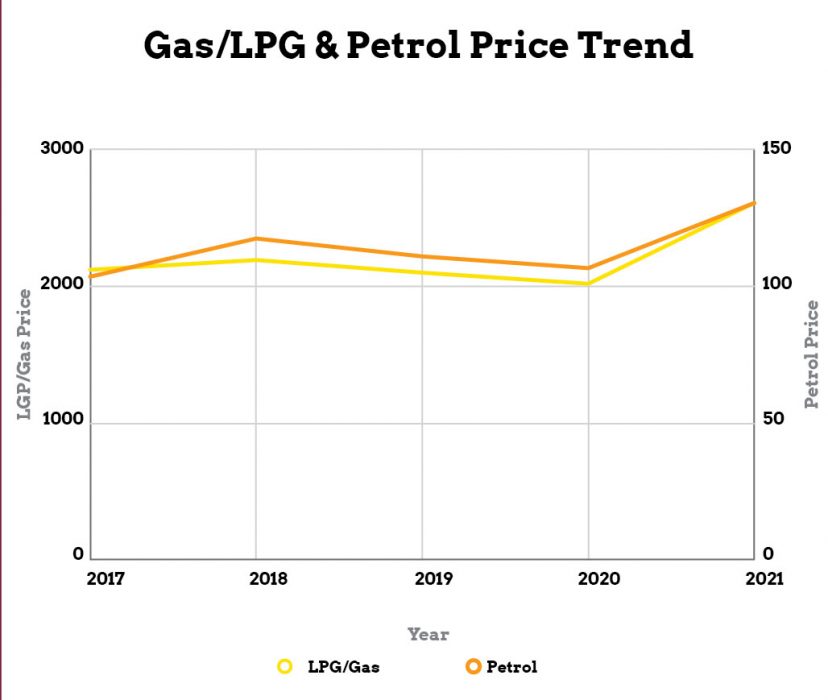

In September 2021, fuel inflation rose to 11.1 percent. This was around the same time Kenya recorded an all-time high fuel price of KES 135 for a litre of petrol. The global prices are high partly because of a choke on production by the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The growing demand for oil worldwide has outpaced supply as economies recover from restrictions and shutdowns prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In November, the price of Brent crude, the international benchmark, traded at more than $84 a barrel, its highest since 2014.

Another notable price increase has been that of cooking oil. The retail price of cooking oil has increased by about 44% since November 2020, owing to the rise in prices of edible oils after a global surge in palm oil price in 2020. Kenya is a net importer of raw and intermediate materials used in edible oils, with most of its palm oil coming from Indonesia and Malaysia. In mid-March 2021, Malaysia’s (the second-largest palm oil producer) benchmark crude palm oil price touched $1,007.30 a tonne (Sh108,587), the highest since 2008. Additionally, bad weather and labor shortages triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic continue to depress palm oil production in Malaysia. The higher price of cooking oil has exerted upward pressure on food inflation, given the essential nature of the product in most meals.

Another variable affecting food prices is the high demand for food to fill the party tables by consumers after the pandemic lockdown. During the December festivities, demand for specific goods such as certain foods or consumer goods increases, causing the demand curve to shift outwards. As long as an increase in supply does not accompany this, prices remain high this Christmas.