Here is the thing about viruses. They are always playing a cat and mouse game with the immune system. You see, a virus is like one of those characters you encounter in a SciFi movie. Weird and eeky. Parasitic in nature, viruses have a basic structure, with only a protective protein coat housing it’s genetic material which they use to corrupt the cells of the organisms they invade.

Once a virus enters the human body, it crafts a way to survive the vicious attacks from the ever vigilant immune system. Considering that the immune system is like the proverbial watchman of the human body, the best way viruses play the evasion game against the immune system is by mutating.

Mutation works just like the lizard of old, the chameleon, changing its colour to evade capture by blending into its surroundings. That’s how viruses drive scientists and the immune system nuts, by becoming invisible. These mutations can sometimes persist and never go away. But at other times, they simply show up and quickly make their exit from the human body. The COVID-19 virus is no exception.

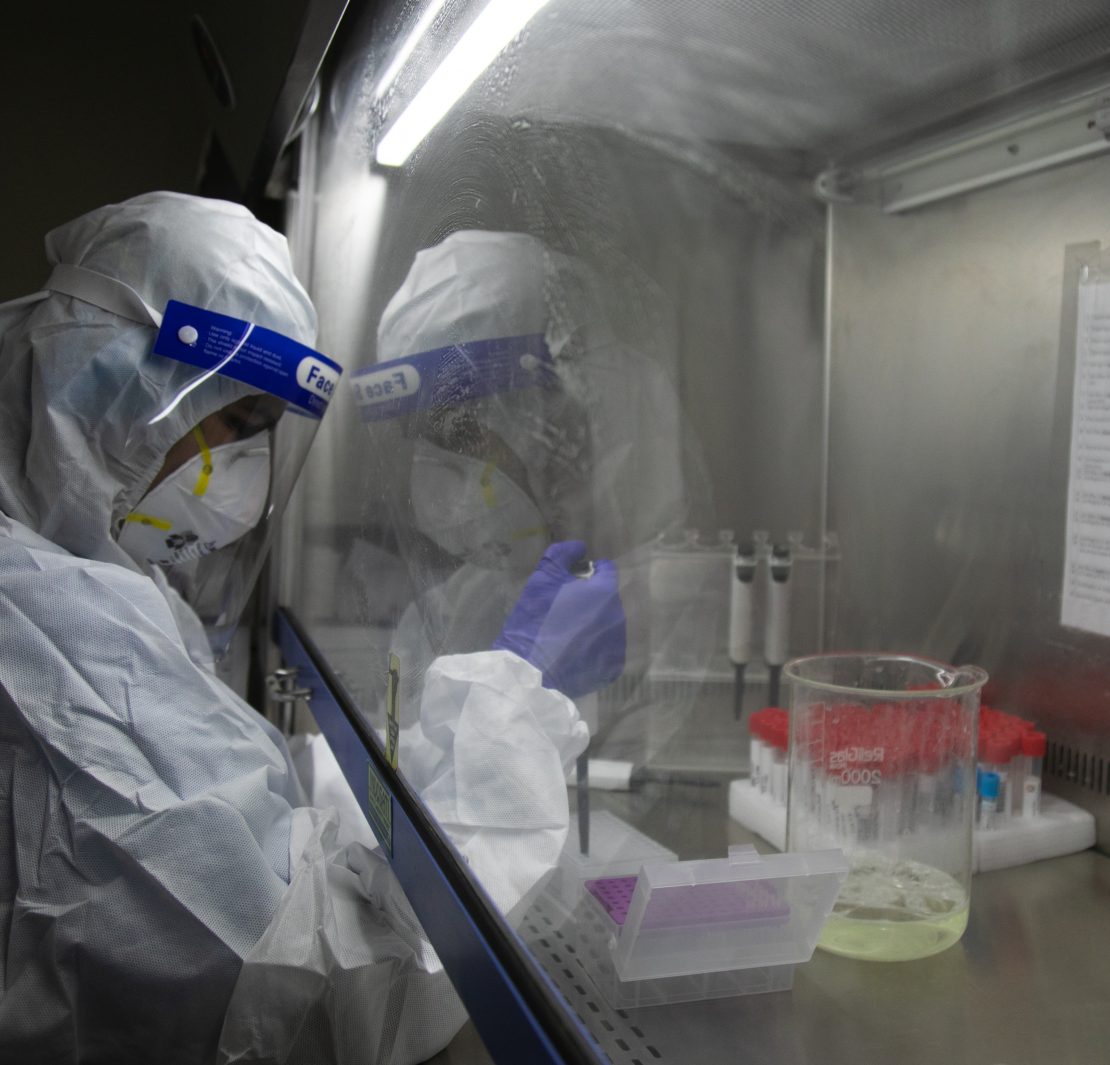

While researchers were busy studying the virus, the virus was also studying the human race. Such that, as progress was being made on probable vaccines, thousands of viral mutations were already happening. Some of the new variants have been proven to be more lethal than earlier versions of the virus, while other mutations have been established to have had little or no effect on COVID-19 as we know it.

The first case of a new COVID-19 variant, B117, was reported in Kent in the United Kingdom in September 2020. Since then, this particular mutant has spread across the UK, and has been reported in other countries. In the panic wave that followed, countries such as France and Germany took mitigatory measures such as closing their borders temporarily for travellers from the UK.

While some countries enforced strict customs regulations, others such as Kenya are yet to close any of their borders to the UK. Recently, I had the rare opportunity of having a tete-a-tete with the Cabinet Secretary for Health, Mutahi Kagwe. During the brief interaction, I asked the CS if closing Kenya’s borders to entrants from high-risk jurisdictions was an option, even if of last resort were COVID-19 mutations to persist.

Kagwe’s response was in the affirmative.

“There is no measure that we are not prepared to take,” the Cabinet Secretary said. “There is no measure at all and you know it won’t be the first time that we have done that; if you remember when in March and April we had closed those borders. So, there is no measure that we can not take to protect our people.”

As much as the CS is ready to take further measures, we hope we won’t get there.

According to The Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal, the new B117 variant has had a significant number of mutations, 23 to be exact. Researchers have pointed out that these mutations could change how the spike proteins on the surface of the COVID-19 virus bind to human cells. The spike proteins are like different keys that open up the human cell and aid the virus gain entry into the cell and start its replication process. Scientists have discovered that the new variant has a high transmission rate of 70%, meaning it can be easily spread. The good news is that the B117 variant doesn’t seem to make people sicker or increase chances of fatality.

Of all African countries, South Africa has had it rough. The emergence of the new 501.V2 variant – discovered in the Nelson Mandela bay area in October 2020 before quickly spreading across the country – has made things particularly difficult, with 90% of all new COVID-19 cases in the country resulting from the variant. The good news is that just as the variant discovered in the UK, the 501.V2 South African variant doesn’t make a person sicker or increase the risk of death.

Dr Anthony Fauci, an immunologist and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease in the United States recently pointed out during a live broadcast by the National Institute of Health that, “The one from the republic of South Africa is a little bit more complicated because some of those mutations might have a negative impact on the efficacy of some of the monoclonal antibodies that are used. So, we are looking into that very carefully”.

Much as it may seem like humanity is fighting a losing battle against COVID-19, scientists remind us that every organism is built to adapt and that that is no exception to viruses. Like viruses – which have greatly mutated since antiquity – the human race too with its thousands of years of existence has adapted to various hostile conditions multiple times. This is therefore one more scenario in a line of many where like a game, the virus makes a move and humanity counters that move.