The headaches came and went like the current melancholic Nairobi weather. At first, Mara Moja pain pills did the trick and allowed me to work peacefully with ‘Time Flies’ by Burna Boy acting as a soundtrack to my creativity. But as time progressed, my body needed something stronger. That was how my addiction to Tramadol, a prescribed opioid pain med that I got from my mother’s after-surgery pack, became part of my daily routine.

It was a cold Wednesday. The lack of my usual go-to-pills from my mother’s medicine pack landed me in the hospital hoping for a quick refill and off to my big client presentation later in the day. The glass mosaic in the doctor’s office neither uplifted nor reassured me of my health. I was seated across from the doctor as he read my charted symptoms by the triage nurse a few minutes earlier.

“How bad are your headaches,” he asked, still perusing through my file and looking at my medical history. My ailment had metamorphosed into different things for the previous four months of that year. It only became an unsolvable problem with over-the-counter medication when all my headaches were accompanied with nausea and shortly after, projectile vomiting that left me weak and helpless in the office, at least three times.

As I sat there narrating to the doctor the different scenarios of the same symptoms, I could tell he was unsure of my diagnosis. His elimination process began. “Have you done a pregnancy test?” I laughed and assured him I didn’t need one. He carried on with his elimination questions and we landed on a blood test as the next best option for a proper diagnosis. I was not particularly thrilled with this route of diagnosis but my unhappiness was embedded in my distaste for sharp things poking my skin.

My injection was a quick less-than-5-minute affair escorted with judgemental looks from the nurse who administered the blood withdrawal on how hysterical I was. Upon entry to the cold and half-filled waiting room, a happy one-year-old greeted me. Her only interest was learning how to move around the room with the help of the chairs and the knees of strangers. As I walked past the mother intently feeding her baby, a half-peeled banana and disregarding the germs in the hospital, I felt my footsteps getting louder and louder as I neared the back of the room, furthest from the motion box at the front. My headaches were back for their frequent visits.

Before I could settle on my window seat, the nurse shouted my name from the door and my journey back to the doctor’s office had to begin. “There isn’t anything in your blood. Your white cell and the red cell count are both normal.” I was disappointed in the answers and my face communicated the same. “I am, although,” (phew, please salvage the situation) “going to write a prescription that will deal with your headaches.” I immediately told him that the only painkiller that seemed to do its job was Tramadol. I could see the shock in his eyes.

Without hesitation, the doctor aggressively cancelled his writings on his prescription pad and paused. “Joan,” he said with a tone of concern, “have you experienced blurry vision when you are having your episodes?” I nodded, too fearful to admit it. The doctor then proceeded to write someone’s name on a clean pad. “He is an expert and will be able to find out what the issue is.” He smiled but his voice wasn’t reassuring as he probably intended it to be.

I left the doctor’s office with no answers and now I had to take matters into my own hands. Dr Google had to come to my rescue. On my way to the Nelson Awori building, as instructed, Google had already given me answers. According to my search, I had a brain tumour. I was hysterical. The Uber driver noticed. “Madam, uko sawa?” My mind couldn’t formulate an answer.

I could be having a brain tumour for goodness sake!

I alighted with urgency and made my way into the building after checking for the doctor’s office on the notice board. I finally had a chance to calm my mind on the possibility of death as I was in the elevator alone. Then, suddenly, I craved my go-to painkiller that had run out.

Out of the elevator, I opened the doctor’s door, hopeful that this is where I get my supply. This office was different from the previous doctor’s office. An aquarium was situated next to the receptionist and the latest health magazines lay around. I gave the receptionist my note and she notified me that the only way to see the specialist was through an appointment. Her further instructions included doing an MRI exam first before my consultation, seeing that my problem was neuro-related. We settled on the following week.

I headed back to work, sat at my desk and my next memory was me in an open room separated by curtains, an undeniable detergent scent, a lady with a stethoscope around her neck with a white long coat and my sister standing close to my bed. As I slowly came out of what I gathered from everyone – a fainting spell – there was my sister, wearing concern on her whole body, and a doctor who introduced herself and asked me how I was feeling and what was happening before my collapse.

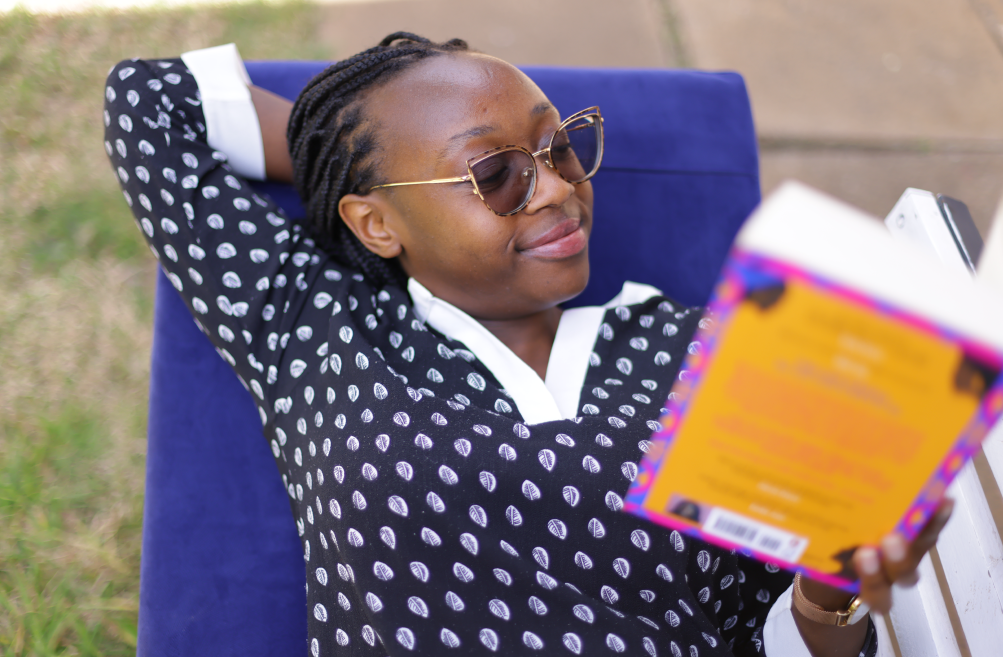

That was the beginning of my mandatory 5-day bed rest, away from all technology, books and most importantly work. My only connection to the world was the periodic visitations from my family and a conversation with the hospital’s on-call therapist, whose main conversation with me involved learning how to rest, mentally more than physically.

According to the therapist, younger people experienced burnout more than in previous generations. She related millennial burnout to imposter syndrome despite it being an unusual correlation. My case wasn’t so foreign to her, she said. Burnout rates as the years progress are on the rise. In fact, in a study reported in 2022, the burnout rate went up to 52% in employees. As I sat in the blue-washed room, facing the white and pink lily pictures hanging across the hospital bed. I began to recount the steps that led to my hospitalisation.

My bedrest involved small doses of distraction like the hospital chatter that was loudest during visiting hours, the nurse’s station banter and the occasional bird visits to the tree next to my window.

On my last day of admission, other than being grateful to not have a tumour and that my overdependence on pain meds was over, I was also eager to return home and reunite with my noisy, overly-involved but loving family.

But before the doctor could write my discharge papers, she sat on my bed, her black dress slipping past the lab coat and asked how I felt about work. Through the mandatory sessions with my therapist, my perception of work had changed. I had learnt that rest is a much-needed aspect of staying alive. After listening intently to my answers, nodding along to my new revelations, she said, “I hope you will always remember one thing in this life after all is said and done.” She stood up to declare the prominence of the statement she was about to make. “Rest is brutally as important, if not more than work.” I heard her. Loud and clear. You should too.