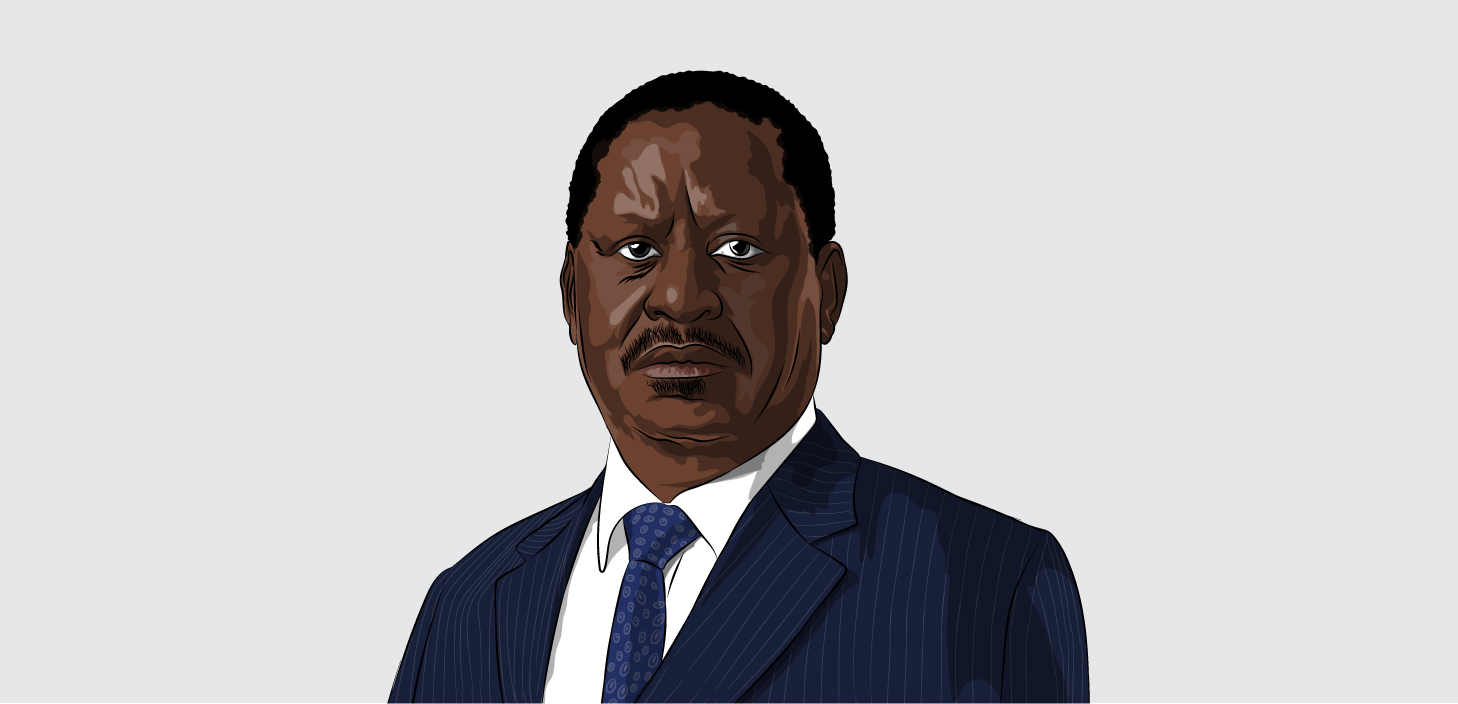

In July 2006, at a time when Kenya was hurtling towards its most contentious presidential election pitting the opposition’s Raila Amolo Odinga against incumbent Emilio Mwai Kibaki, Nigerian academic professor Babafemi Badejo released Odinga’s biography titled Raila Odinga: An Enigma in Kenyan Politics.

Those who read read the book – certainly many didn’t – but the net effect of Badejo’s endeavor was that Odinga went into the fever pitch 2007 presidential campaigns having acquired yet another moniker – enigma. To Odinga’s supporters, who knew him by various epithets; jakom (chairman), agwambo (mystery man), among others, skeptics could say whatever they wished to say about their man, but the verdict was out. There was only one enigma in Kenyan politics. His name was Raila Odinga.

The mystery, or is it the mastery, was real.

Four years earlier in December 2002, Odinga had made one of the most consequential endorsements in Kenyan political history when during a packed rally at Nairobi’s Uhuru Park, he proclaimed ‘’Kibaki Tosha,’’ two words which galvanized the country behind Mwai Kibaki’s candidature. On his third run, Kibaki was catapulted into the presidency.

It had happened that not too long after Odinga’s affirmation, Mwai Kibaki was involved in a near-fatal road crash on his way from a campaign rally. As an indisposed Kibaki was dispatched to London for treatment, Odinga took over the reins of the campaign, crisscrossing Kenya as if he were running for president himself. As Odinga and others were securing the victory, Kibaki jetted back into the country to be sworn-in as president, on a wheelchair. As a mark of gratitude, Kibaki’s supporters baptized Odinga njamba (warrior).

But beyond the mystery and the mastery, something else was revealed about Odinga during the 2002 campaign. Michael Kijana Wamalwa, who rose to become Kibaki’s vice president, remarked tongue-in-cheek that Odinga was the only Kenyan politician to attract love and hate in equal measure, thereby resulting in two phenomena, Railamania and Railaphobia.

To Wamalwa, Odinga was the sort of character who could be uniting just as he could be polarizing, a man who had built a one-of-a-kind fanatical core support base which stuck with him whether he won or lost elections. The converse, according to Wamalwa, was that such a near-religious following would attract an equal and opposing force in the form of detractors.

Wamalwa would know. He and Odinga had a history.

Odinga, Wamalwa and Kibaki had all run for president in 1997, with Kibaki, who was running a second time, coming second with 30%, while Odinga and Wamalwa, who were running for the first time coming third and fourth with 11% to Odinga and 8% to Wamalwa. Strongman Daniel arap Moi, who had ruled Kenya since 1978 when he took over following the death of founding president Jomo Kenyatta, retained the seat with 40%.

It was under these circumstances – of the divided opposition having lost to a less popular Moi a second time since the reintroduction of multipartism in 1992 – that in June 2001, Raila Odinga shocked both friend and foe when he announced he was entering into a cooperation deal with Moi. Odinga had been Moi’s longest political detainee, but now the victim and his oppressor were making peace. It reeked of opportunism – Moi pulling in Odinga to sanitize his regime’s stinking past, and Odinga and his squad going in to raise political budget and use the state for future political advancement.

And so Odinga merged his National Development Party (NDP) with Moi’s independence party the Kenya African National Union (KANU), to form New KANU, with Odinga as secretary general. Odinga was appointed minister for energy, lasting for a year and a half before Odinga led a mass walkout after Moi bypassed him and handpicked Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Moi’s predecessor Jomo Kenyatta, as his preferred successor.

This last minute move by Moi made it impossible for Odinga to run for president in 2002. Odinga could only crossover and join the three uniting opposition leaders; Kibaki, Wamalwa and Charity Ngilu – who had garnered 7.8% in 1997 and come fifth.

The Wamalwa-Odinga history went even deeper.

In 1994, following the demise of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, Odinga’s father, Odinga and Wamalwa went head-to-head against each other over who was to succeed Jaramogi as leader of the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD) – Kenya. One version of events is that Wamalwa won that battle, the other is that Odinga exited before Wamalwa could win.

The real import of 1994 is that the real Raila Odinga stood up, no longer eclipsed by his father’s towering shadow.

*

Raila Odinga left Kenya for East Germany aged 17 in 1962, dispatched by his East-leaning freedom fighter father Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. Jaramogi, the quintessential larger than life persona, had started out as a young intellectual at Makerere University. But on sensing that he had a dangerous politics, the British colonialists denied Jaramogi a scholarship to study in London. Raging with frustration, Jaramogi watched as his contemporaries, the likes of Kenya’s first Black lawyer Argwings Kodhek received scholarships and left for London.

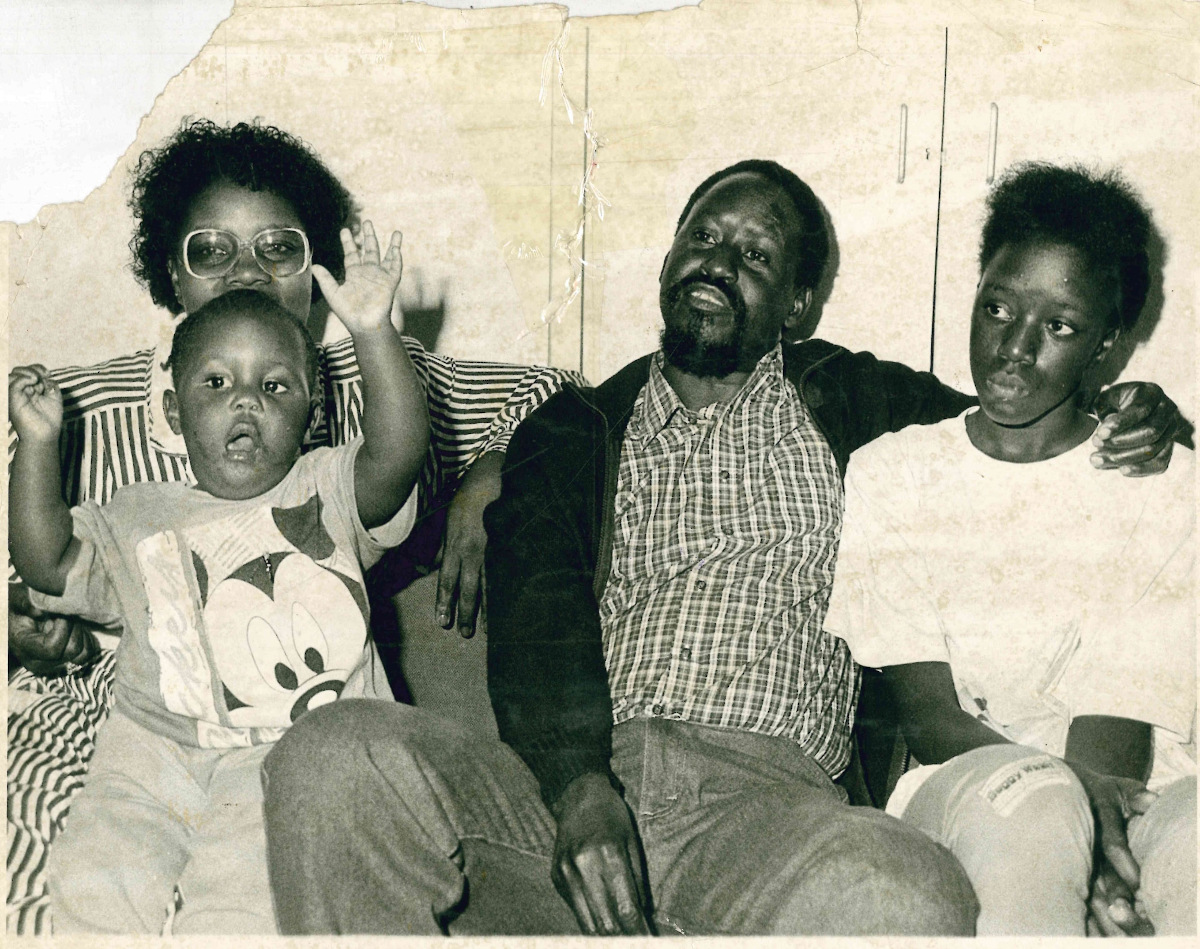

With no route to further his studies, Jaramogi retreated to Maseno School, his alma mater, where he became a teacher and started a family. It was in Maseno that Jaramogi birthed his second son Raila in 1945, named after Rayila, Jaramogi’s grandfather. Keen on making something bigger out of his talents, a broke Jaramogi resigned from Maseno soon after and started mobilizing his Luo kinsmen to start a business.

The Luo Thrift and Trading Corporation was born.

It was in the process of seeking to make the Luo an economic powerhouse through the communal company that Jaramogi came to the inevitable realization – just like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkurumah and others – that the pursuit of economic emancipation without political power was a pipe dream.

Jaramogi switched gears to politics.

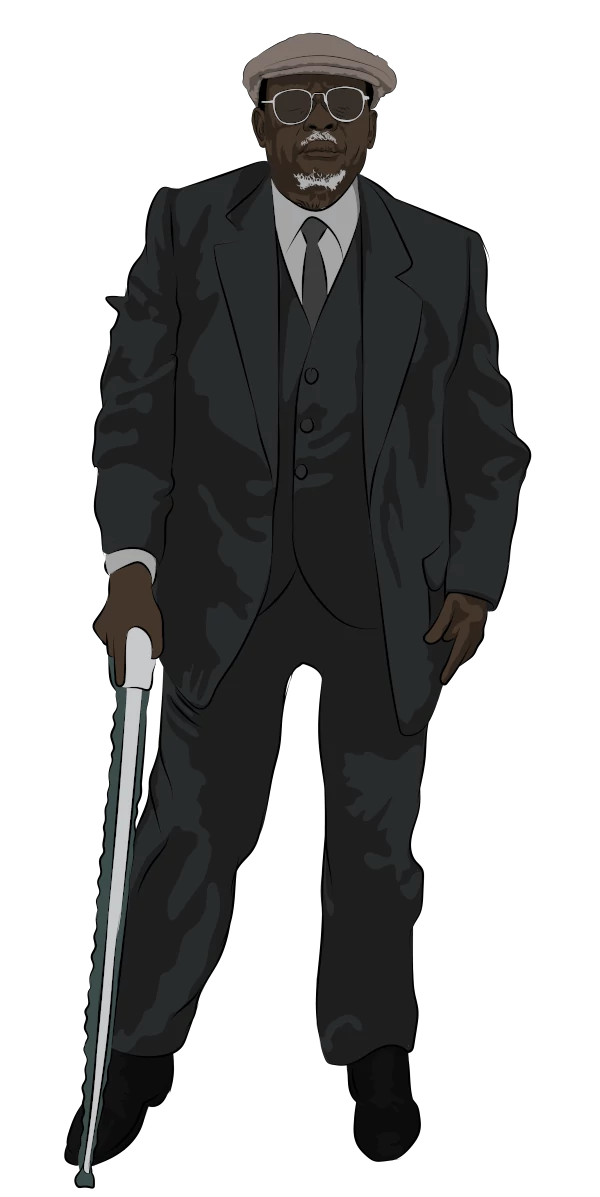

It was with this backdrop that Jaramogi morphed from being a utopian Maseno-based trader who first shook the hand of the already-famous Jomo Kenyatta in 1948 in Kisumu, to becoming a household name as Kenyatta’s and independent Kenya’s first vice president fifteen years later in 1963.

Jaramogi had a superpower.

While attending the Alliance High School, Jaramogi’s British principal Edward Carey Francis had asked the ever-mobilizing young man a pertinent question. ‘‘Why this need to organize, organize, organize all the time?’’ Francis couldn’t understand Jaramogi’s need to always bring people together for whatever cause, unaware that that was Jaramogi’s superpower – from organizing the Luo to organizing nationally and regionally.

Raila Odinga took after his father’s superpower.

By the time Odinga was returning to Kenya in 1970 after studying engineering at the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg, Jaramogi had already fallen out with Jomo Kenyatta and Kenya had suffered near-irreparable damage.

Barely two years after becoming vice president, Jaramogi had resigned from government citing the untenability of his position. Just like his successor Joseph Murumbi who resigned three months into job, Jaramogi was an egalitarian who not only looked East, but together with Murumbi and others, sought answers over land redistribution and events such as the assassination of their comrade Pio Gama Pinto.

Considered Jaramogi’s right hand man and Murumbi’s mentor, Pinto had played a huge role in Kenya’s independence struggle, and his killing had left more questions than answers regarding Kenyatta’s government. When the colonialists had asked Jaramogi to bypass Kenyatta and form government while Kenyatta was still imprisoned, Jaramogi had turned down the offer as an act of loyalty. Now he and others were pariahs.

Things took a turn for the worst on 25 October 1969.

The Russian government had funded the construction of a hospital in Jaramogi’s Kisumu backyard, and Jomo Kenyatta insisted on launching it. The timing couldn’t have been worse.

Four months earlier on 5 July 1969, 39 year old minister for justice Tom Mboya, who was the senior-most Luo in Kenyatta’s government at the time, was assassinated. Mboya, a Jaramogi rival in Luo politics, was seen as a potential future president, a threat to Kenyatta. Mboya’s death had shaken the Luo.

In January of the same year, Argwings Kodhek, a renowned lawyer and Jaramogi confidant, had died in a mysterious road accident in Nairobi. These, coupled with the detention of Jaramogi’s top associates by Jomo Kenyatta, fuelled the narrative that the Luo were under siege by the government.

And so when Jomo Kenyatta stood to speak in Kisumu in 1969, starting off by admonishing Jaramogi, the crowd booed and surged. The presidential guard opened fire, killing and injuring an unconfirmed number of civilians, thus the Kisumu Massacre. Jaramogi was placed under house arrest, and never reconciled with Jomo Kenyatta until Kenyatta’s death in August 1978.

Kenya was never the same again.

And so as Raila Odinga started teaching engineering at the University of Nairobi in 1971, the fortunes of the Jaramogi household were dwindling at a faster rate than Odinga’s salary could withstand. Odinga sought an under-the-table loan from an Indian banker – bailing out Jaramogi’s family was an affront to the state – with which loan he established Spectre Limited, the only company manufacturing gas cylinders in Kenya.

Three years later in 1974, the Kenyatta government extended some leniency to Odinga, allowing him a job at the Kenya Bureau of Standards, where he rose to become deputy director in 1978. However, Odinga’s mind was in politics.

On the morning of 1 August 1982, a group of Kenya Airforce mutineers led by Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka attempted to overthrow the government of Daniel arap Moi. On inheriting the presidency in August 1978 following Jomo Kenyatta’s death, Moi had promised to follow Kenyatta’s footsteps. Ochuka and his men wouldn’t give Moi time to properly locate the footsteps.

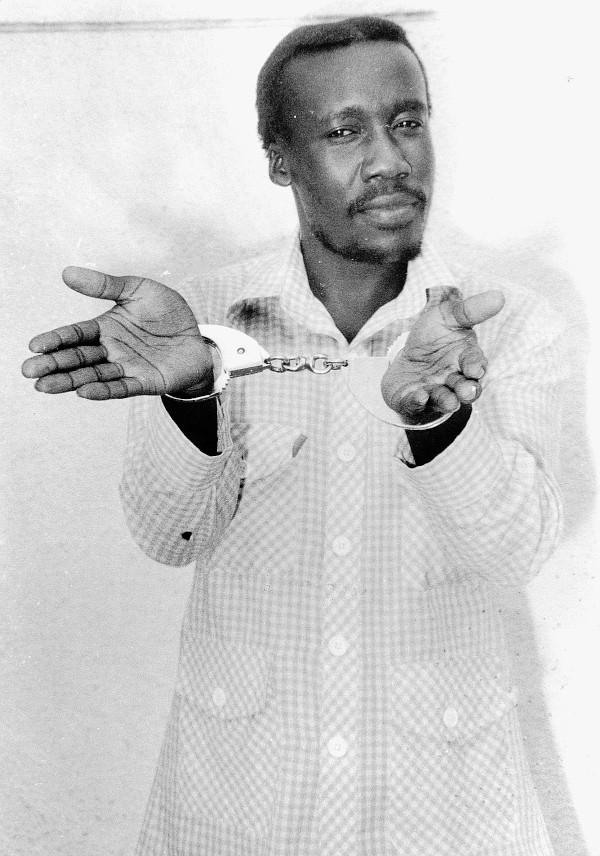

After the coup was quashed and Ochuka and others put on trial and hanged later on, among those who a ruffled Moi went after was Jaramogi and his son Odinga. Being a bit lenient, Moi consigned the 71 year old Jaramogi to house arrest while he charged Odinga with treason. Odinga was taken into detention on suspicion of having played a role in the coup.

Theories abound as to Odinga’s involvement in the coup or lack thereof, but on his part, Odinga never speaks straight about the events of the day, for obvious reasons.

It had happened that two months before the coup, in July 1982, Moi had turned Kenya into a one party state upon hearing that Jaramogi was planning to register a socialist party, with the help of University of Nairobi lecturers who had written the manifesto. And so speculation was rife that the coup had been a reaction to Moi turning Kenya into a one party state.

As Odinga and others would learn, getting Moi and his party KANU out of power wasn’t easy. It would take them 20 years from 1982 to 2002, when Odinga would say ‘’‘Kibaki Tosha’’ and have Moi’s successor Uhuru Kenyatta lose the election. But if Odinga had had dreams of being president aged 37 in 1982 – that is if he was part of the coup matrix – then Odinga must have learnt by now that to be president isn’t easy. It might just have taken him a cool 40 years since 1982 to become president in 2022, if at all.

*

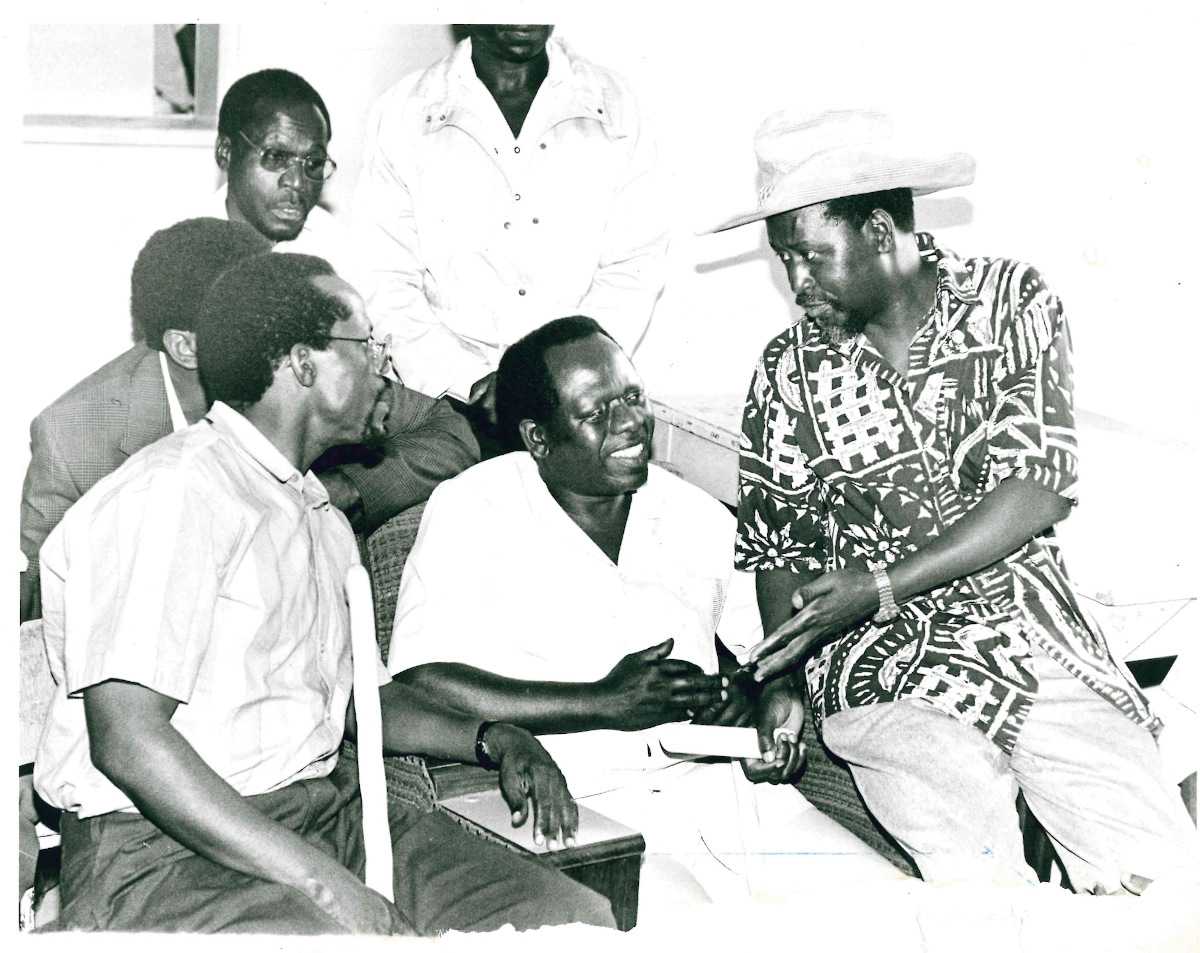

Before he died on 20 January 1994, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga called a group of young men into his hotel room. Among them was Paul Muite, Michael Kijana Wamalwa, James Orengo, Prof. Anyang’ Nyong’o, Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi, Gitobu Imanyara and George Kapten. Jaramogi gave the group a series of coded messages, and thanked them for sticking with him to the hilt.

This group, alongside Odinga and others, became the renowned Young Turks who fuelled Kenya’s second liberation. Odinga’s only downside was that he had spent the bulk of his time in detention while the group gelled. This proved costly.

After Odinga was released from detention in February 1988, six years after his 1982 arrest, Moi rearrested Odinga in September of the same year, on suspicion that Odinga was joining forces with the pro-democracy movement, demanding for the return of multipartism. Back from his second stint in detention in June 1989, Odinga got word that he was facing imminent assassination, and fled the country through Uganda, disguised as a Catholic nun.

Broke and without a plan, Ezra Bunyenyezi, the Ugandan owner of Uganda Travel Bureau who had offered crucial behind-the-scenes support to the likes of Yoweri Museveni and Paul Kagame during their liberation struggles, bought Odinga a one way air ticket to Norway, where Odinga landed at the residence of his comrade Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi’s parents-in-law.

As Odinga was fleeing, Dr. Kituyi and the Young Turks had turned Jaramogi’s Agip House office into their operations base. Working with other pro-reform forces, they would soon force Moi to repeal Section 2A of the Constitution in December 1991, allowing the return of multipartism. The reformists were operating under the aegis of a pressure group, the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), with Dr. Kituyi as founding executive director.

By the time Oidnga was back and the December 1992 general election was happening, FORD had become a political party and split into two, with Jaramogi and the Young Turks going one way and Kenneth Matiba – who had just returned from treatment in London after suffering a stroke while in Moi’s detention – leading a splinter group at his Muthithi Road office.

There was FORD-Agip and FORD-Muthithi.

Odinga joined his father’s party.

It was under these circumstances that when Jaramogi died after coming fourth in the elections with 17% – Matiba was second with 26% and Mwai Kibaki third with 19% – a leadership tussle ensued. Paul Muite, the then chairman of the Law Society of Kenya, was Jaramogi’s first vice chairman, with Michael Kijana Wamalwa being the second vice chairman. Odinga was the party’s director of elections, and MP for Langata in Nairobi.

Just before Jaramogi died, Muite had exited the party over allegations that a financially struggling Jaramogi had accepted a cash donation to the party from Kamlesh Pattni, the mastermind of Goldenberg, the biggest financial scandal of the early 90s. Muite’s exit thus meant Wamalwa became Jaramogi’s first vice chairman, and technically his heir apparent.

But just as Jaramogi was accused of taking money from Kamlesh Pattni, who was being investigated by parliament, Odinga too accused Michael Kijana Wamalwa of accepting a bribe from Pattni, and asked the party to purge Wamalwa from its leadership. A leadership contest ensued, and Wamalwa, who had the full support of all the Young Turks who had attended the meeting in Jaramogi’s hotel room, became chairman.

The matter wasn’t that straightforward.

At a personal level, Odinga had more struggle credentials than Wamalwa. After all, Odinga was Kenya’s longest serving political detainee. On his part, Wamalwa, the British educated lawyer and son of a former senator, was seen as a happy-go-lucky smooth operator. He was one of Kenya’s finest multilingual orators who enjoyed life on the fast lane, and was perceived as lacking political discipline, running his affairs in a laissez faire manner. Wamalwa’s saving grace was that he too had his die-hards, seduced by the man’s mien and irresistible charm.

The dynamic within the Young Turks was that they viewed themselves as worldly intellectuals. They liked the finer things in life even if they were in the trenches, quoted Shakespear, and enjoyed speaking Kiswahili sanifu among themselves and at rallies to wow crowds – with those having difficulties with the language hiring Kiswahili tutors. They also waxed lyrical about the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks.

Raila Odinga seemed removed from these banalities and trivialities. It was either that Odinga was power hungry and/or impatient, or that he thought the Young Turks lacked agency to deal with the more urgent revolutionary matters at hand.

Odinga’s further alienation came from the fact that almost the entirety of the Young Turks were lawyers and social scientists. He was the only engineer. The other elephant in the room was succession in Luo politics, in which case Jaramogi had a favorite in James Orengo, a fiery MP and former president of the University of Nairobi student guild.

Orengo, debonair and fearless, had delivered a powerful speech titled ‘Woe Unto Thee’ at Jaramogi’s burial, targeted at Moi and other persecutors of Jaramogi, accusing them of shedding crocodile tears at the funeral. So fiery was the speech, in vintage Orengo style, that everyone feared Orengo’s arrest was imminent. The revered Weekly Review published the speech verbatim.

That speech, and Jaramogi’s widely known affinity for Orengo, who was effectively Jaramogi’s son – Jaramogi and Orengo’s father were contemporaries at Maseno School – situated Orengo as the future leader of the Luo within the Young Turks.

And so in the tussle between Odinga and Wamalwa, Orengo supported Wamalwa, who was Orengo’s Law lecturer at the University of Nairobi, and Wamalwa supported Orengo to become his first vice chairman. Other consequential Luo figures such as Prof. Anyang Nyong’o and Jaramogi’s longest serving right hand man and Jomo Kenyatta’s prison mate, 72 year old Ramogi Achieng Oneko, all went with Wamalwa, possibly seeing Odinga’s move as an unnecessary, premature rocking of the boat. Odinga was undeterred.

Raila Odinga resigned from the party in a huff, thereby forfeiting his Langata MP seat, precipitating a by-election. Odinga took over the moribund National Development Party, through which he successfully defended his parliamentary seat. With that one act of defiance, Odinga sent a warning shot to the Young Turks, especially those from his Luo background. Odinga, a master of the ground-game, went on overdrive.

In Kisumu – now Kisumu City, the seat of power for the Luo, mayor Akinyi Oile had built a serious ground force, which Odinga rented. There were emergent groups such as Baghdad Boys, who were controlling political rallies and such. Odinga went deep down and consolidated the ground as much as he could. By the time he was running for president in 1997, Odinga had displaced the Nairobi-group led by the likes of Orengo.

Odinga’s party won a substantial number of parliamentary seats in his Luoland, 21 in total, with the likes of Anyang’ Nyong’o and Ramogi Achieng Oneko, who had sided with Wamalwa, losing their seats. James Orengo survived.

It was with this new mandate – as Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s substantial heir coming complete with a parliamentary party, that Raila Odinga cut a deal with President Moi and merged their parties. Odinga was keen on getting as far ahead of the rest of the Young Turks as he could. Every card – including working with Moi, his repeat jailer – was on the table.

By the time Odinga was falling out with Moi and saying Kibaki Tosha in 2002, Odinga had consolidated his business empire and finished any pending assignments in his coronation as the official king of the Luo. James Orengo, Anyang’ Nyong’o and others would have to toe the line or risk political oblivion.

*

There’s a point during his political rallies where Raila Odinga turns into a football commentator. Two teams will be playing, one with Odinga as captain and another led by whoever is Odinga’s main challenger during a presidential race. Odinga starts off by giving the ball to the opposing team, which passes it around and almost always fails to score. Odinga’s side then takes the ball, passes it around, before Odinga, who is always playing as a striker, gets a pass and scores the winning goal.

This is a leaf off Raila Odinga’s political rule book.

In his political calculations, it is as if Odinga always wants to come from behind, as if turning tables on his opponents offers a better thrill and allows him to plot and move in silence.

The deal with Mwai Kibaki in 2002 after the Kibaki Tosha moment was that Kibaki would usher in a new constitutional order and make Odinga prime minister, but Kibaki reneged. Odinga became minister for roads, before his 2005 fall out with Kibaki over Kibaki’s faulty draft constitution. Kibaki kicked Odinga out of government, gifting Odinga the underdog position as he moved towards the 2007 presidential election. Before Kibaki realized what a massive mistake he had made, Odinga had created a massive national anti-Kibaki wave. This was the time Odinga was being called an enigma.

By the time the votes were streaming in, it was clear Kibaki had lost his parliamentary majority to Odinga. The electoral commission started performing a circus as it tallied the presidential vote on live TV, before the commission chairman was whisked away by armed police into a secret room, where only the national broadcaster was allowed in. Kibaki was declared winner and sworn in just before dusk, a first in Kenya.

The country exploded.

It took Koffi Annan’s delicate mediation to quell the violence and facilitate a handshake between Odinga and Kibaki on the steps of the president’s office at Harambee House – the same spot where Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta would announce a cease fire ten years later. Odinga became prime minister.

The belief was that as the second most powerful individual in government after Mwai Kibaki, Odinga would march towards the 2013 presidential election with an upper hand.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

As if allergic to having a head start, Odinga watched as internal dissent rocked his party, resulting in William Ruto, a politically shrewd Moi and Odinga protege who had been essential to Odinga’s 2007 campaign, exiting the party. Ruto would later become Uhuru Kenyatta’s deputy president in 2013.

And as if the losses within the party weren’t enough, more chaos unraveled at the office of the prime minister. Power struggles between Odinga’s advisor Miguna Miguna and Odinga’s chief of staff Caroli Omondi resulted in Miguna’s dramatic exit, coming complete with a tell-all book on the drama inside Odinga’s machine. Tony Gachoka, Odinga’s chief of protocol, quit citing power tussles. To crown it all, corruption allegations at Odinga’s office surfaced, forcing Odinga to suspend both his permanent secretary Mohammed Isahakia and chief of staff.

By the time Kenyans were voting in August 2013, Odinga was facing a formidable threat from deputy prime minister Uhuru Kenyatta and Odinga’s one time political student William Ruto.

The premiership hadn’t yielded much advantage.

And just like he would do in 2017 when Kenyatta and Ruto were declared winners, Odinga went to the Supreme Court in 2013, but the piece of evidence his lawyers considered the smoking gun was disallowed after it was filed outside of procedure.

Kenyatta and Ruto took office in 2013, and weren’t keen on losing to Odinga come 2017, only that this time round Odinga presented a watertight electoral fraud case and was met with a bolder, Bible-wielding Chief Justice David Maraga who bit the bullet and nullified the presidential vote.

But still, Ruto and Kenyatta – and it has since emerged that it was more Ruto than Kenyatta – wouldn’t let the presidency go. When Odinga boycotted the repeat presidential election, Ruto and Kenyatta ran against themselves and were sworn in.

Odinga defiantly swore himself in on 30 January 2018.

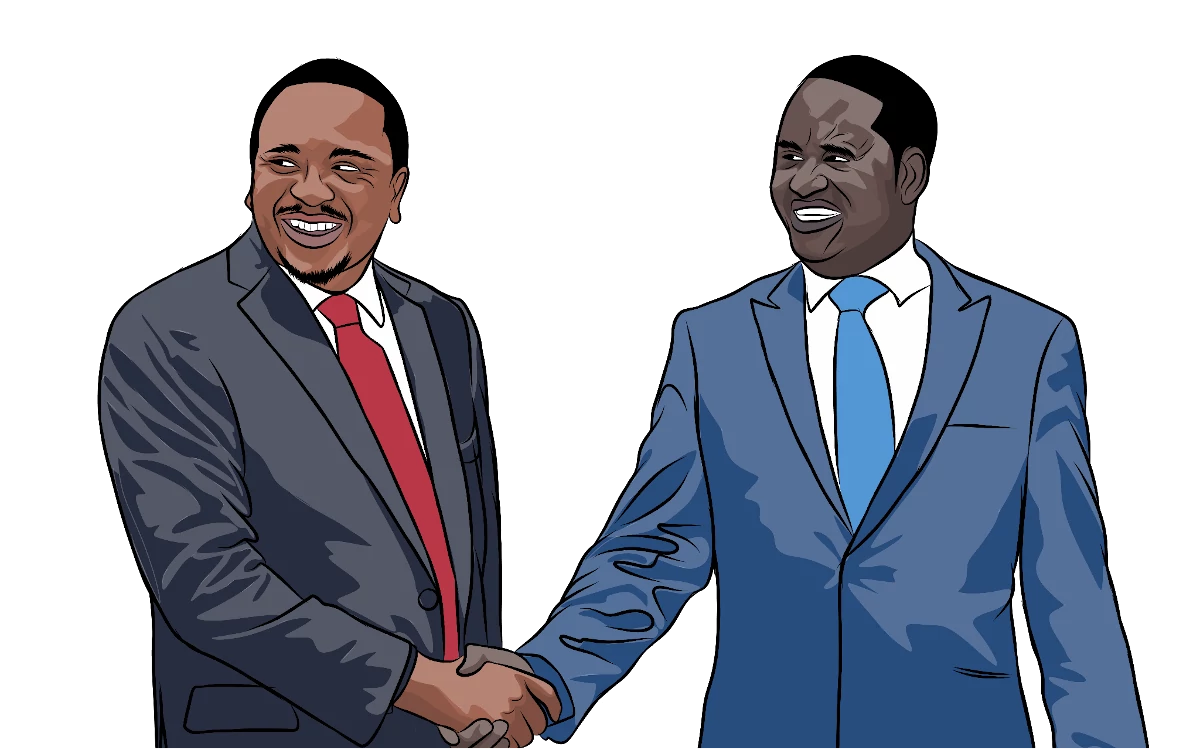

It was out of this stalemate – of Odinga’s supporters protesting and threatening to make the country ungovernable unless the election was revisited, and Kenyatta feeling he had a legitimacy deficit and a potential turncoat in Ruto – that the son of Jomo Kenyatta and the son of Jaramogi united on 9 March 2018.

An unstructured man-to-man and family-to-family pact, the two sons diagnosed Kenya’s problems back to their fathers falling out, and promised to do everything within their powers to right the wrongs of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

The product of that process was the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), an omnibus project proposing 76 constitutional amendments. BBI was struck down by the high court, the court of appeal and the supreme court. Among other things, Odinga and Kenyatta were proposing an expansion of the Executive, to bring back a prime minister – possibly Kenyatta – among other positions. William Ruto opposed every Odinga-Kenyatta move.

As a comeback, Kenyatta and Odinga changed the law to allow for the creation of a super-political party, a party of parties, with Kenyatta as chairman and Odinga as its 2022 presidential candidate. As if to atone to the Young Turks, as his running mate, Odinga picked Martha Karua, one of their struggle comrades. Known as the iron lady of Kenyan politics due to her courage and no nonsense stance, Karua, who served as Kibaki’s minister for justice before resigning, brought into the ticket new impetus, what the Young Turks would call electricity.

With Odinga’s new sobriquet being Baba (father), the Odinga-Karua duo became the Baba na Mama (mother) ticket, with Baba na Martha being the more palatable reference.

The enigma and the iron lady have mellowed.

But true to form, Odinga came into the game late, finding Ruto had already made major strides. But after playing catch up with the support of President Kenyatta, who endorsed Odinga, Odinga and Ruto are now neck to neck at the eleventh hour.

At 77, it is do or die for Raila Amolo Odinga. All the mystery and the mastery must come to bear, or the fall for both Odinga and President Kenyatta will be harder and heavier, presenting an untidy ending to the whole Jaramogi-Jomo Kenyatta affair.

The clock is ticking and tocking.

An edited version of this article was first published in The Continent, the award-winning pan-African newspaper.

Subscribe for free here: https://www.thecontinent.org/subscribe