On 13 August 2021, four young men were murdered in Kitengela by mob justice on suspicion that they were cattle rustlers. Days later, Riki, a member of the Wanavokali music group was arrested while walking in downtown Nairobi with his bandmates. Luckily for Riki, his Wanavokali bandmates live-streamed the arrest on their Instagram page, insisting Riki’s only crime was that he was rocking dreadlocks, just like three of the four deceased in Kitengela whose murder alongside Riki’s arrest has sparked discourse about hair, specifically dreadlocks on men.

It was the same old conversation about whether dreadlocks are decent or not.

The discussion exposed the perception that society has of dreadlocks – that locks are dirty, unprofessional and worn by the unruly. It was disheartening to read remarks such as “men who keep dreadlocks are not serious in life” that continue to endorse colonial legacies, such as the myth that dreadlocks are dirty, on black hair even among the youth. And these legacies do not just affect men with dreadlocks but anyone who dares rock their natural hair unapologetically.

Mungiki, a banned sect in the country, did not help in making a case for men who don dreadlocks. In 2007 at the height of the crackdown against it, men who had dreadlocks were often believed to be members of the group. If anything, it furthered the perception that dreadlocked men are dangerous and are likely to break the law. Even after the Mungiki members stopped wearing locks, the stereotype that any man who fronted the hairstyle was a thug or a delinquent persists.

Still and all, if you look at it and how our society is set up, it is not entirely a surprise that those perceptions exist. Hair profiling is not a contemporary issue. It has its roots in the epochs of colonial days and in the missionary schools which outlined rules that controlled how students should look. The regulations required the students to straighten their hair through laborious processes like blow-drying, chemical relaxers or instructed the students to shave their hair off. These requirements were in place and are still in place to ensure “uniformity.”

As society becomes more aware of the irrationality of these rules, schools are having to lax the regulations or are forced to do it. For example, in 2019, a student was expelled from Olympics High School because she had dreadlocks. However, her family successfully sued against the expulsion. The courts ordered the school to reinstate the student, saying the expulsion violated the freedom of religion, specifically, the Rastafarian belief.

Sharon Akinyi from Kisumu faced similar problems in 2018 when St Mark Obambo Secondary School failed to admit her unless she shaved off her hair. The school said that students had to wear short hair because of the hot and dusty environment. Nonetheless, Akinyi, with a Bible in hand, used the same tool missionary schools used to make a case against shaving her hair. Quoting 1 Corinthians 11:14-15, a verse stipulating that the length of a woman’s hair is her glory, Akinyi said she would rather forego high school education to join a polytechnic than go against the Lord.

Far from school, the same legacies are still subtly endorsed in the corporate world.

Newton Wesonga, a tattoo artist based in Kilifi tells a tale of how he wore a turban to cover his dreadlocks as a banker. During my tattoo appointment, Newton narrated how he was not allowed to have dreadlocks working as a banker but to beat the system, he used the same tool Sharon Akinyi used. He wore a turban to work and invoked religion until the day he resigned.

Furthermore, Newton told me his two children have dreadlocks but are currently in a British school in Kilifi that does not restrict them the freedom to wear a natural look. Coincidentally, it is easy to spot a student from plush private schools with natural hair or hairstyles prohibited in public schools. It is almost as if the right to rock black natural hair is a preserve for the bourgeoisie.

The portrayal of natural hair or dreadlocks in the media is also telling. While the media publishes numerous stories that criticize the stereotypes on dreadlocks, presenters or news anchors who don natural hair are often a rare sight. Most times, the men who have dreadlocks in the media are behind the scenes as videographers, radio presenters, producers or editors.

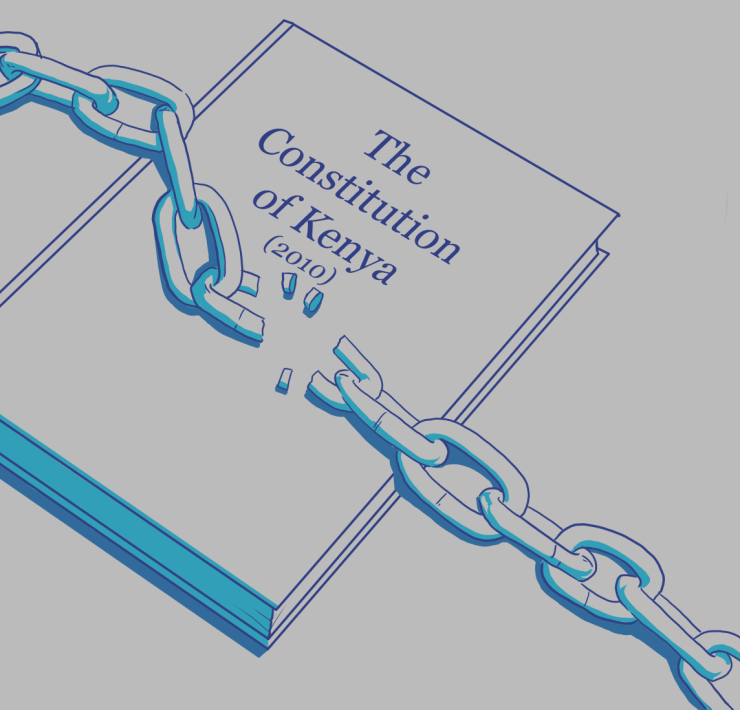

The same discourse on dreadlocks has permeated the legislative world. It was an unusual sight when a dreadlocked student, Mathenge Mukundi graduated from Kenya School of Law in 2020. Similarly, lawyer Bobby Mkangi was surprised when the Public Service Commission selected him on the Committee of Experts that drafted the constitution. According to the article above by the Nation, Mkangi was aware that his dreadlocks posed a challenge in the selection process.

But according to lawyer Mark Nduati, dreadlocks are not disallowed in the courts as long as they are neat.

“There is a shift from conservatism to liberalism in the legal profession as far as what is considered a professional look,” Mark says. “Even though we do not see active litigating lawyers with dreadlocks, dreadlocks are allowed in the courts as long as they are neat.”

Even though afros, braids and dreadlocks are welcomed as fashion statements in less formal sectors, the maintenance of such hairstyles is risibly expensive. In a country where almost everyone’s hair is nappy, it is uncanny that grooming natural hair to look natural is one of the most expensive ventures.

Case in point, it costs an average of twelve thousand to have the hairstyle known as Sisterlocks. These microlocs, which are thinner than traditional locks, cost a dime to start and maintain. Dreadlocks, too, are not any different, especially during the installation process. And let’s not talk about the cost of hair products for anyone who wants to maintain their afro or natural hair without using any relaxers.

For one Brenda Musimbi, who decided to stop blow-drying her hair three years ago, the journey of having her hair as natural as possible is not only expensive but also marred with snide comments by hairdressers. If not told to blow dry her hair, Musimbi is always asked to use a hair relaxer to make her hair “manageable.”

“It is not easy for me to find salons that offer natural hair solutions,” Musimbi says. “It should not be that difficult or expensive to maintain my hair.”

It is easy to shift blame to institutions when it comes to hair profiling. The perception against natural black hair is the ripple effect of successful indoctrination done by colonizers. But, if anything, isn’t the notion that natural black hair is unprofessional or dirty against the gospel of love that the colonizers so proselytized?