There is a song for every moment, including the frequent moments in Brazzaville, Congo’s capital, and Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s capital, where espousing an extravagant fashion sense is a way of life for a certain group of individuals.

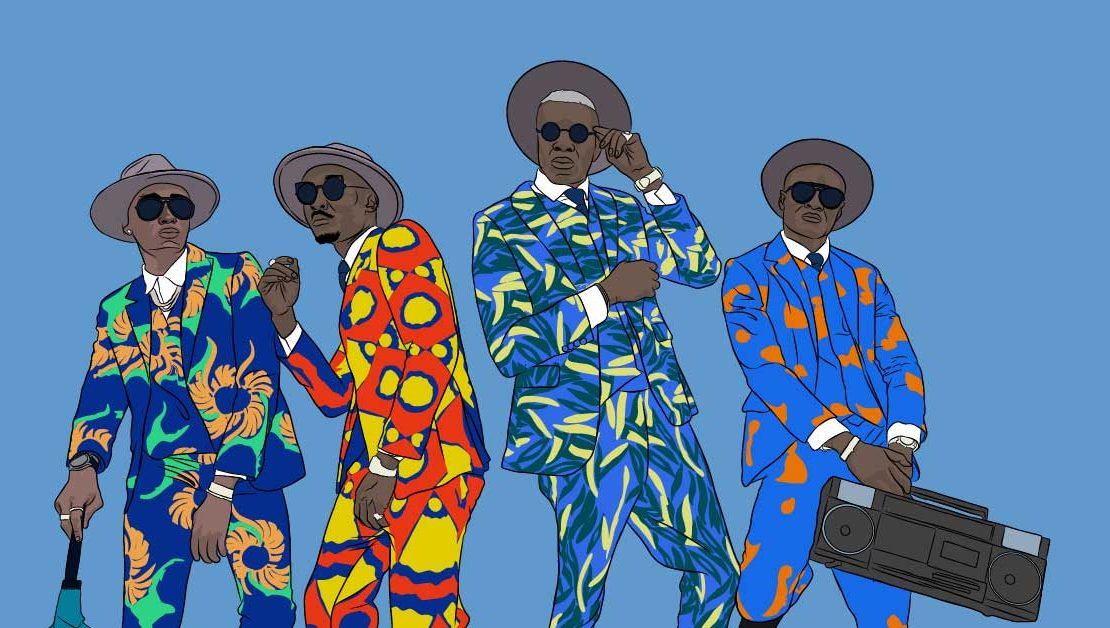

This is the part where a Papa Wemba song is cued. Red velvet curtains are lifted and out comes a row of men and women dressed to the nines, each boasting a different colored suit, hat, cane, luxurious designer loafers, sunglasses and a distinct walking style that is the perfect synonym for energy, passion and enthusiasm.

In all these features they are communicating, their audience left in awe.

These men are Sapeurs and the women Sapeuses, and they have come to slay.

Sapeurs are part of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes, or if you like, the Society for the Advancement of Elegant People. If either feels too long for pronunciation or memory, you may simply say La Sapé. La Sapé isn’t just a moment of fashion and exuberance. La Sapé is a lifestyle with origins in the late 19th century.

The Original Sapeur

The record shows, and rightfully so, that Andre Matsoua was the godfather of Black African Sapeurs. Born in 1889 in ‘French’ Congo, Matsoua was one of a handful of Africans in both the colony and the continent who received a Western education before it was commonplace, curving himself a promising career as a churchman.

At the time – and as is the case today – literacy was continually fashioned for the elevation of the colonizers (strangers in Matsoua’s ancestral land), a knowledge system meant to oppress indigenous communities. This skewed state of affairs awakened something within Matsoua: curiosity, frustration and a burning desire to do something about it.

Political Matsoua

And so Matsoua chose not to pursue his studies any further after attaining a basic qualification. He made his way to ‘French’ Morocco as one of the Senegalese Tirailleurs troops recruited to fight in the Rif War (1921–1926). After the war ended in 1926, Matsoua made his way to Paris, where he connected with other African immigrants from French colonies on the continent, and was ushered into the world of trade unions. In this political awakening, Matsoua saw the need to emancipate his home country from French rule, and together with other like-minded Africans formed Black-based trade unions.

Matsoua’s fire was likely fuelled by his learning that inequity and brutality were the order of the day in other African colonies. Needless to say, this regenerated his frustration and initial desire to seek change in the Congo.

That year, 1926, Matsoua conceptualized and started a movement to gain self-rule from France using peaceful means. The movement, L’Amicale des Originaires de l’Afrique Équatoriale Française (today known as Matsouanism), aimed to create an elite version of the status of the white man and effectively gain independence from France. Matsoua’s work and dedication came to be known by Africans in Congo who sent financial contributions to his cause, a project which they strongly believed was leading them on the road to independence.

The Oppressor Strikes

But Matsoua’s efforts were unexpectedly halted in 1929 when he was arrested and charged with exploiting Africans in ‘French’ Congo for their money. Matsoua was set to be tried in Brazzaville, and so he was deported to the Congo in 1930, where he faced colonial administrators at the Court of Brazzaville (according to Italian Fashion Photographer Daniele Tamagni, Matsoua was arrested while in Congo), accused of anti-colonialism.

Surprisingly, and maybe as a strategy to make his tormentors see him as an equal, Matsoua’s one request to the Court was that he be tried as a French citizen, citing that he had been living in France and was arrested in French territory. This did not work in his favor because, in April 1930, Matsoua was sentenced to three years in prison and banned from ‘French’ Congo for a decade. A week later, Matsoua’s exile had been decided. He was banished to Fort Lamy in Chad, where he was ordered to spend ten years.

Escape and War

Matsoua was not one to be held prisoner especially for a crime he believed he hadn’t committed, and so he escaped and made his way back to France. While it is not clear when exactly he skipped banishment, Matsoua was once again on the battlefield in 1940 during the Second World War in north eastern France, fighting against the Germans.

Unlike the Rif War, this time Matsoua was not so lucky. He was wounded at the battlefront and sent to Beaujon Hospital in Paris, where he received care. Another missing fragment of Matsoua’s story is that in April 1940, he was arrested for allegedly attacking French state security officials. The consequence? Matsoua was once again expelled from France and sent to Congo, where his verdict was handed down nine months later, in which he was condemned to forced labour in Brazzaville in February 1941.

This was the beginning of the end for the original Sapeur.

Downward Spiral

Barely a month later, Matsoua faced allegations of distributing pro-German pamphlets, a crime that attracted further punishment. Matsoua was once again jailed, and with a record as a repeat offender to his name, he inevitably became a target, even behind bars. Sources say he was tortured and beaten, succumbing on 13 January 1942.

The Fire Lived On

Matsoua’s name would not be forgotten, nor would his attempts to peacefully see an independent Congo. His influence on other Africans in both ‘French’ and ‘Belgian’ Congo was a fire that could not be put out. It was the birth of La Sapé. And even after the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo both gained independence in June and August 1960, the Matsouanism movement was still alive, active and vibrant.

Matsoua’s influence and La Sapé heightened during the Mobutu Sese Seko regime (1965–1971/1971–1997) as a form of rebellion, reacting to the Mobutu Sese Seko’s nationalistic policy of repression.

Papa Wemba Picked the Baton

Beyond the political realm, a legend who in some ways followed in Matsoua’s footsteps and influenced the Sapé–surge is renowned Congolese singer Papa Wemba, who was born a few years after Matsoua’s death. Wemba’s music and style showed an evolution of La Sapé, as well as elevated it such that it was a Congolese trademark, but one that would influence several Africans who admired the flamboyance.

This is where the question of the current La Sapé lifestyle comes into question.

From Wemba’s glorious days to date, La Sapé is said to be a way “Congolese people express themselves and make a statement during times of instability.” A way for the people to see themselves as overly modern, and thus, everyday Congolese are spending most of their money (and then some) on globally famed designer brands such as Cartier, Givenchy and Gucci. Those unable to buy the lavish brands settle for easy–to–miss imitations.

Some say “life as a Sapeur is nothing but extravagant fashion choices.”

Would it then be wise to say that the original goal of Matsoua, with his choice to dress like the Europeans, has been wishy-washed over the years, evolving with time to become all aesthetics without politics? Perhaps. But as the tunes play and the Sapeurs straddle, there should be an acknowledgment of what this culture is truly about; the freedom, resistance and revolution the lifestyle is rooted in, in memory of Matsoua, the logician whose life was snatched away from him for simply starting a peaceful liberation movement shrouded in fashion.