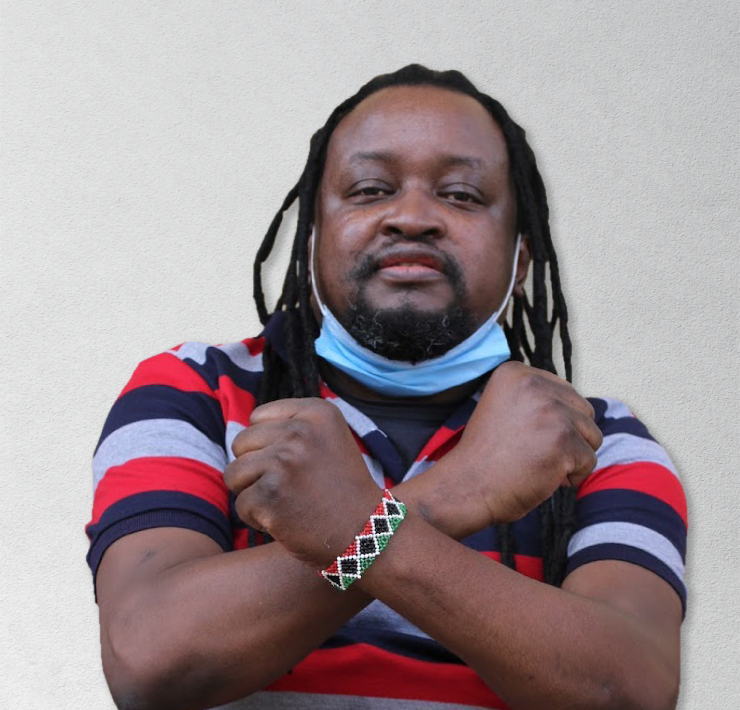

WANJIRA WANJIRU is a grassroots activist who co-founded the Mathare Social Justice Centre and the Matigari Youth Book Club. She is a BA student at the University of Nairobi and co-host of the Liberating Minds podcast on YouTube and SoundCloud. Wanjira was nominated as human rights defender of the year in 2020 for raising awareness about extrajudicial killings by the police, and has been featured in Al Jazeera’s Generation Change, the Guardian and the New Humanitarian. RASNA WARAH spoke to her about her work in Mathare and the challenges facing female activists in Kenya.

Q. You rose to prominence on Saba Saba day in 2020 when a video of you defying a police officer went viral. Kenyans were shocked to see a young woman looking a police officer in the eye and saying, “I’m protesting because you are killing us.” But we don’t know what happened after that. Were you arrested?

No, I wasn’t arrested. I joined fellow protesters at the rooftop of Ukombozi Library. That day was beautiful because we had real class solidarity. University students from USIU [United States International University] and Daystar joined other youth from informal settlements to commemorate Saba Saba and say together that we demand better. We had a few speeches and reflections and then I went home.

Q. Your motto is, “When we lose our fear, they lose their power.” When I saw you in that video, I was reminded of another fearless woman, the environmentalist Wangari Maathai, who was often beaten up by the police for protecting forests and fighting for the freedom of those who were illegally detained by the Daniel arap Moi regime. How difficult is it being a female activist in Kenya?

Wangari Maathai is our hero, we remember her always and celebrate her great spirit of resistance. She is a great inspiration and role model. We live in a patriarchal society and that is one of our major challenges as women in general. But Prof. Wangari Maathai demonstrated that we can always maneuver when we employ creativity as a tactic. Like when she added an ‘a’ to Mathai when her ex-husband asked her to drop his name. Or when she told Moi we are not using the anatomy below our waist but above the neck, challenging him intellectually. The other major challenge is time, as it is often difficult for women to balance home, family, school and activism as well as make time for hobbies and fun.

Q. You were born in Mathare, one of the poorest informal settlements in Nairobi, which has been the site of hundreds of extrajudicial killings by the police. Your own elder brother, Damason, was killed there. Is he the reason you, with others, started the Mathare Social Justice Centre?

No, it was the normalisation of these killings that birthed MSJC. My brother was just one of many. Almost everyone in Mathare has lost a dear one to police killings. A son, a father, a brother, a friend, a cousin, or an uncle. It’s like a cleansing of the youth. Every time we met as friends, it was the same narrative of killings in our different wards in Mathare. Senior comrades advised us to start a social justice centre to challenge the normalisation of organised violence against our people. With time, we got to see it’s not just in Mathare but in Kayole, Githurai , Kariobangi, Kibera and these communities, which also started their own justice centres. We came together to amplify our struggles and demand for dignified lives, as promised in Article 43 of the Constitution on economic and social rights. As Franz Fanon said, “Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfil it or betray it.”

Q. Your centre records and documents extrajudicial killings and other atrocities committed by the police. How has your work helped raise awareness of the problem, and have these killings reduced as a result? What has been the reaction of the National Police Service to your work?

Our work has helped stop the normalisation of police killings in Mathare and now at the national level. The other day President William Ruto admitted that there is a police killer squad that will be disbanded. IPOA [Independent Police Oversight Authority] has finally prosecuted “killer cop Ahmed Rashid” who was notorious for extrajudicial killings. We would love to see him in court given the many lives he has taken in the name of maintaining law and order. I can say these killings have reduced significantly. Previously, we wouldn’t go a week without documenting a case, but now we can go for months. But the high cost of living and unemployment are a major concern. When the Kazi kwa Vijana program ended, we documented 14 cases of extrajudicial killings in one month. There is a significant link between poverty, survival and bullets.

Q. Why do you think that young men in Mathare and other poor neighbourhoods are so vulnerable to police violence?

There are no opportunities for youth in Mathare and other ghettos to make a living. Poverty makes you vulnerable, it is the highest form of violence because you’re locked out of basic needs like food, water and shelter. These are primary needs and must be met somehow. The police know that these youth have limited opportunities and, therefore, some steal for survival, which is honestly what they do to get by, but I have always wondered why the mega thieves who loot and plunder the country don’t suffer the same fate as the petty thieves. I condemn the petty thieves but even the grand ones; they steal our future, our well-being, our wealth and we wallow in poverty a little more while they gain a lot more. I long for when we will truly see each other – the street child, the mama mboga, city askaris, hawkers, students, great men and women. I hope we soon recognise that our well-being here and now is more important. I long for the day when dignity becomes a birthright for all, wherever they are from. The commonalities amongst us human beings are a real power for social change if harnessed and actualised.

Author

-

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist with over two decades of experience as an editor, writer and communications specialist. She wrote a weekly op-ed column for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, for many years, and has contributed to various regional and international publications, including, the UK’s Guardian, Africa is a Country, The East African, The Mail and Guardian, The Elephant, and Kwani? She has worked as an editor and writer at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and has published two books on Somalia: Mogadishu Then and Now (2012) and War Crimes (2016). Her first book, Triple Heritage (1998), explored the history of South Asians in East Africa. Her latest book, Lords of Impunity (2022), examines the failures and internal contradictions of the United Nations and what can be done to transform this global body. She holds a Master’s degree in Communication for Development from Malmö University in Sweden and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and Women’s Studies from Suffolk University in Boston, USA. She is based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist with over two decades of experience as an editor, writer and communications specialist. She wrote a weekly op-ed column for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, for many years, and has contributed to various regional and international publications, including, the UK’s Guardian, Africa is a Country, The East African, The Mail and Guardian, The Elephant, and Kwani? She has worked as an editor and writer at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and has published two books on Somalia: Mogadishu Then and Now (2012) and War Crimes (2016). Her first book, Triple Heritage (1998), explored the history of South Asians in East Africa. Her latest book, Lords of Impunity (2022), examines the failures and internal contradictions of the United Nations and what can be done to transform this global body. She holds a Master’s degree in Communication for Development from Malmö University in Sweden and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and Women’s Studies from Suffolk University in Boston, USA. She is based in Nairobi, Kenya.