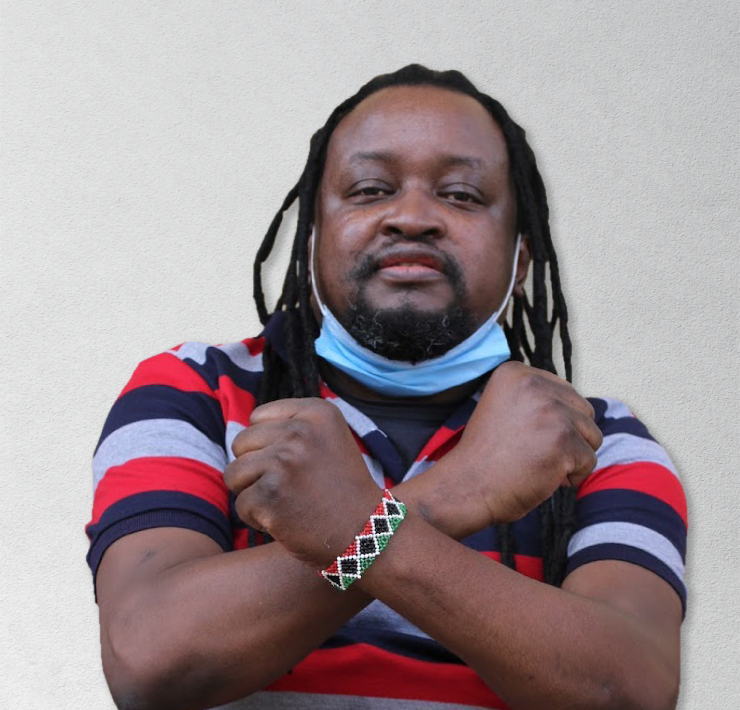

SITAWA NAMWALIE is a Kenyan poet, playwright, and performer known for her unique dramatised performances that combine poetry and traditional Kenyan music. Before she became a performance artist, she was a tennis star and environmentalist. She spoke to RASNA WARAH about her writings on race and tribe and why she believes it is a dangerous time to be a woman today.

Q. Your background is in environmental science and development work but you decided quite late in your career that you wanted to be a writer and poet. How did this transformation come about?

I always wanted to be a poet and writer from when I was a child. But I also wanted to be many other things and I was good at many things. When I was 14 years-old I decided to be an environmentalist and I became one, surprisingly.

Q. Cut Off Your Tongue, your collection of poems – which has been performed several times – addresses issues such as tribalism and ethnic chauvinism in Kenya. The collection came out just before the 2007/8 post-election violence. Why do you think tribe has become such an important part of Kenyans’ identity and the reason for so much polarisation, even though in 2003, when Mwai Kibaki became president, we were all claiming our Kenyan identity?

There are several reasons for our tribalism and we can understand it if we hold several, seemingly opposing or contradictory views at the same time. I think we confuse ourselves when we think about such complex issues such as identity from only one place.

Firstly, there is healthy ethnic identity where people learn about where they come from, embrace their culture, their language and so on. This is critical for the development of productive humans, especially for those of us who were colonised and turned against ourselves in very negative ways.

Secondly, negative ethnicity is also natural. Human beings have the ability to create “tribes” and to believe that their tribe is better than others who do not belong to their ethnic group or “tribe”. This is also natural. Under colonial rule, the colonial powers capitalised on this and created rifts and craters amongst us. We have continued with the idea of using ethnicity to further our political and economic agendas because it works. Since Donald Trump was elected president in the USA, I have learned so much about this tendency for people to use “tribalism” for their own ends. They will say the sky is green if it promotes their tribe.

Thirdly, in other African countries and really all over the world “tribe” and “tribalism” are normal. It is the negative fault line that divides us all. It emerges and becomes important when societies and communities are under some form of stress, whether economic or political. And it recedes when there is abundance. In every country there are the specific drivers of tribalism.

Q. Your writings could be categorised as feminist. You have written about the silencing of women and women being blamed when they are sexually violated or raped. Today women in Iran and Afghanistan are literally being silenced simply because of who they are – women. What is the state of the women’s movement not just in these countries but everywhere? Do you feel, as I do, that there is a backlash against women globally?

Yes, I do feel that there is a backlash against women globally. I am also amazed at how brave women continue to be as they fight for their rights, especially in countries such as Iran and Afghanistan where they face death by simply protesting the need to wear a headscarf or voicing their desire to go to school. These are the direct threats. Young women in countries such as Kenya, South Africa, Nigeria, USA, and UK bear the insidious cost of the rights that the older generation won. This is what I believe the murders of young women is all about. They want to turn the clock back because they are so threatened by the rights and power that women have won. It is a dangerous time for women.

Social media has given us an insight into our societies and communities and it is terrifying what men think of women. There are also groups organising against women in various ways, for instance by demonising feminists. It makes me understand that each generation plays its part and that this is an ongoing battle that cannot be won by one generation, even though we wish it could be.

All this negativity is understandable. Patriarchy, after all, is the first organising principle of the human race and most communities around the world invented it. This is quite amazing, is it not? So, the forces that help to keep patriarchy in place are formidable and cannot be easily crushed. But women must continue to fight, as I believe that a system that grabs everything for itself and undermines another group’s ability to contribute to the human story is inherently evil.

Q. Some of your writings are also about race, about being black and an African in a world where white privilege is seen as the acceptable norm. Do you think movements like Black Lives Matter have shifted the racial divide and made people more conscious of their privileges?

I have been surprised at how important Black Lives Matter has been in shifting the racial divide all over the world. I am still asking why. But I am happy about its impact. What I believe is important is that it has broken down walls and there are more non-people of colour and people of colour trying to understand racism.

Racism is our heritage, yet people maintain their “ignorance” about it. And it is ignorance, sometimes willful, other times just part of the systemic ignorance that the world has developed when faced with difficult and complex issues people created. (So contradictory, is it not?)

As a black African woman, I am at the bottom of the racial hierarchy, but my class lifts me up a few notches. This position is valuable even as it is oppressive and frightening. It is valuable in that I can see everyone else’s “truths” up the ladder.

What then is truth? I have found that it is only the “dominant group” in a specific community that determines truth. And then, white men are the only ones who can hold absolute truths, as they are the ones who can define the world. The demonising of wokeness and political correctness in my view is the powerful eliminating the perspectives of others. They want their perspectives, their truth to be the only one and they want to force it onto other people as they had before. That is the status quo that they want.

My position at the bottom is frightening because I can so easily be defined by those more powerful than me, and there are so many up the race hierarchy. I can see just how powerless I can be and how much I am at the mercy of other people’s “truths”.

Q. Early in your life you became a tennis star and even represented Kenya at the 1978 All Africa Games. How did tennis shape your life?

I actually became a tennis and hockey star in my youth and represented Kenya in both sports in several international competitions. They both had a profound impact on my life and my personality.

Hockey is a dangerous sport. I had to be present and be aware of my surroundings and the people I was playing with to manage myself and avoid the danger inherent in the game. Tennis is psychological, you need to tame your mind and make it work for you and not against you. You need resilience and the ability to bounce back from adversity. Strategic thinking and strategy are important in tennis. Being competitive gave me the ability to rise to the top in whatever career I chose.

I learned about racism from sports. Tennis and hockey were dominated by whites and Asians when I started to play them. We Africans faced a lot of resistance, especially from the white community when we started playing these sports as we were literally decolonising them. I was called a monkey by white children when I was competing against and beating them. I was subjected to a lot of unfair practices, and often had no one to turn to. We just got on with it.

I travelled from a young age both in the country and outside, often without an accompanying adult. I gained exposure and learnt how to think for myself. I think exposure is as important as education. What is exposure? Going beyond your small box, your culture, equipping yourself with the ability to engage and relate with diverse people without collapsing or taking things personally.

The ability to be watched/seen by an audience while wearing skimpy tennis clothes, I am sure, also helped me create that elusive quality called “presence”, which serves me as a performer.

Q. You were once known as Betty Wamalwa but decided to change your name to Sitawa Namwalie. Why?

Becoming a poet, playwright and performing artist has been a process of recovery and re-remembering for me. It is going back to my roots and who I am as an African. We can’t go back totally as we have been transformed by our engagement with the world, but we can keep asking the question, “Who am I?” Even as a child I asked this question and eventually when I became an artist I knew I had to go back to my African name — at least I can control that. Sitawa Namwalie are my names, they are not pet names. They are important names for me, as I was named after both my great grandmother on my mother’s side and my grandmother on my father’s side.

Later I found out that many people who make this leap change their names. So, I did not do anything special.

Author

-

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist with over two decades of experience as an editor, writer and communications specialist. She wrote a weekly op-ed column for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, for many years, and has contributed to various regional and international publications, including, the UK’s Guardian, Africa is a Country, The East African, The Mail and Guardian, The Elephant, and Kwani? She has worked as an editor and writer at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and has published two books on Somalia: Mogadishu Then and Now (2012) and War Crimes (2016). Her first book, Triple Heritage (1998), explored the history of South Asians in East Africa. Her latest book, Lords of Impunity (2022), examines the failures and internal contradictions of the United Nations and what can be done to transform this global body. She holds a Master’s degree in Communication for Development from Malmö University in Sweden and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and Women’s Studies from Suffolk University in Boston, USA. She is based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist with over two decades of experience as an editor, writer and communications specialist. She wrote a weekly op-ed column for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, for many years, and has contributed to various regional and international publications, including, the UK’s Guardian, Africa is a Country, The East African, The Mail and Guardian, The Elephant, and Kwani? She has worked as an editor and writer at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and has published two books on Somalia: Mogadishu Then and Now (2012) and War Crimes (2016). Her first book, Triple Heritage (1998), explored the history of South Asians in East Africa. Her latest book, Lords of Impunity (2022), examines the failures and internal contradictions of the United Nations and what can be done to transform this global body. She holds a Master’s degree in Communication for Development from Malmö University in Sweden and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and Women’s Studies from Suffolk University in Boston, USA. She is based in Nairobi, Kenya.