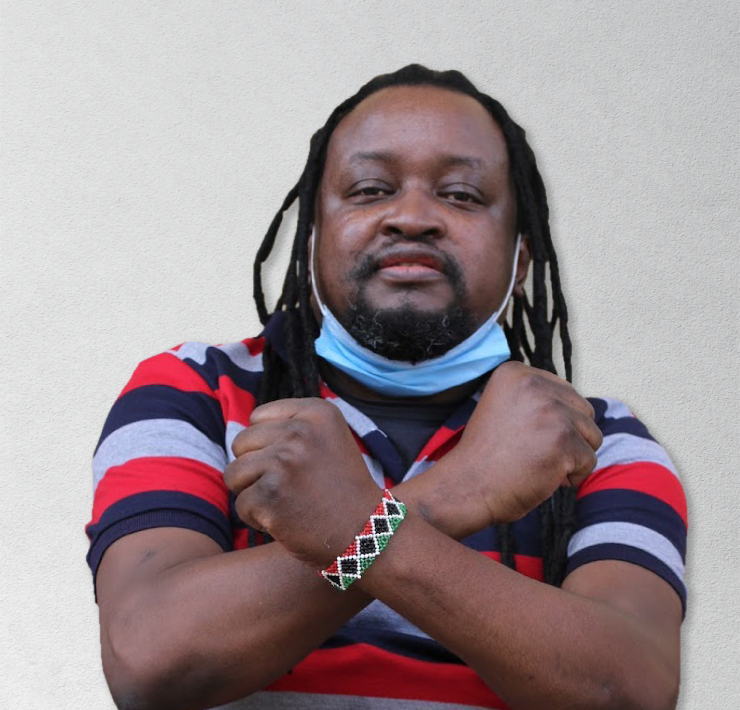

KEVIN MWACHIRO is a Kenyan writer, podcaster, journalist, and queer activist. He has authored Invisible – Stories from Kenya’s Queer Community and was part of the editorial team for Boldly Queer – African Perspectives on Same-sex Sexuality and Gender Diversity. Kevin’s most recent work of fiction is the short story Number Sita, published in the anthology Nairobi Noir. His play, Thrashed, is part of the Goethe Institut’s “Six and the City” collection. In 2017, he launched a story-telling podcast called Nipe Story, which produces audio versions of short-story fictional stories from the African continent. Kevin is also a co-founder of the Out Film Festival, the first LGBTQI film festival in East Africa. He currently serves on the boards of PEMA Kenya, a grassroots LGBQTI organisation, and Amnesty International-Kenya. He spoke to RASNA WARAH about why it is important to recognise the various genders and sexualities in society and how being diagnosed with cancer in 2015 changed his perspective on life and unleashed a creative side of him that had long been suppressed.

Q. On your Twitter handle you describe yourself as a writer, podcaster, journalist, activist, cancer-fighter, proudly queer. Before we get into all that you do and are, can you comment on the anti-homosexuality law that has just been passed in Uganda? Do you think it will have a chilling effect across the East Africa region?

Yes, it has a chilling effect on the community, its allies and supporters. I remember in 2013, the first time the law came into being in Uganda and the day President Yoweri Museveni assented to it, I got a chill and it was scary. My friend Will and I wondered whether something like that would ever happen in Kenya and it felt so far. Ten years later, it seems like Ugandan legislators pulled at all the stops to ensure that this time round there is no opposition.

But we will still be who we are. You can’t legislate how one feels about who one is or how one’s heart skips a beat. I wish society would look at this law from a wider angle and not just see it as a queer thing. There is a similar bill that has been proposed here in Kenya. Instead of creating laws that will ensure and safeguard the rights of sexual and gender minorities, we are seeing legislators passing laws that want to limit our existence and open us to more discrimination and potential violence.

I wish we could be having a conversation on how to educate society on what it is to be LGBTQI so we could normalise our existence and live respectfully with one another. Plus we need to recognise the need for comprehensive sex education in order to open our eyes to the fact that family is no longer just a father and mother and kids.

Things have changed. People are more self-aware of who they are and being gay or queer isn’t a bad thing. It is not a thing to be ashamed of and we should try to see how to incorporate diversity and inclusivity in a way that works for us as East Africans and Africans.

I’d like to believe we live in a forward-thinking region that is full of diversity. We’ve had countries that have rebuilt their nations and economies and reshaped how they look at themselves nationally. All the countries in the region, except Tanzania, have had some form of internal or civil conflict. Too much blood has been spilt in this region, but we have rebuilt and almost reconciled, so why create an environment where we want to go after our own kith and kin for being different? Remember the saying ‘Pili pili usioila yakuwashia nini?’ We are people of utu. It feels like that is being forgotten.

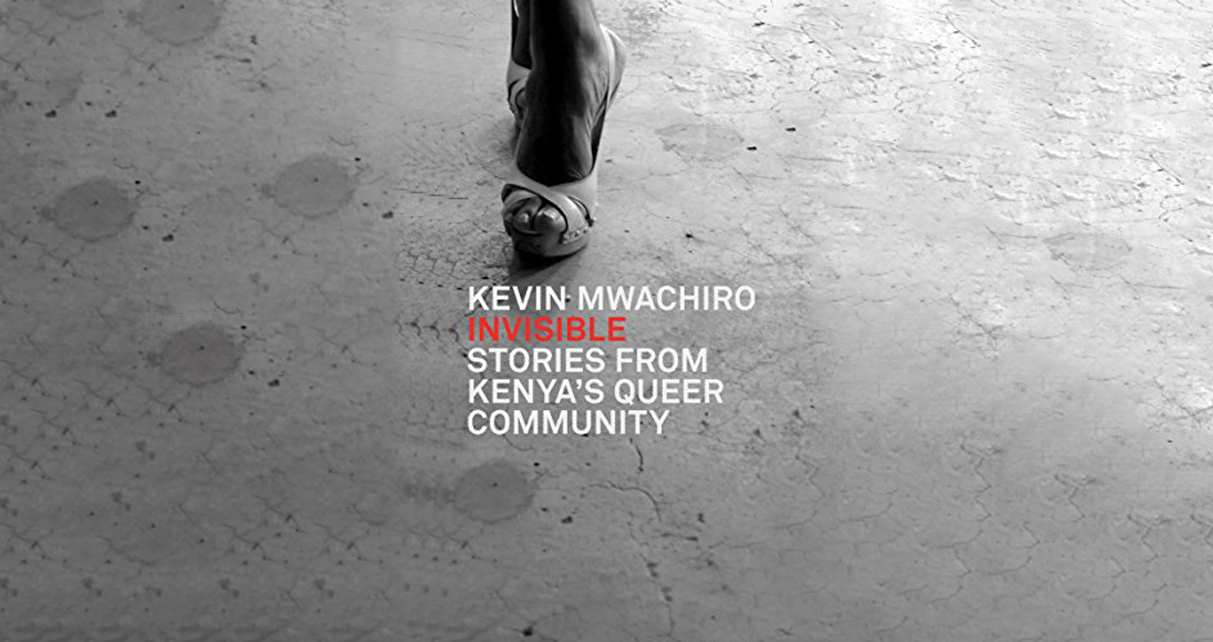

Q. You wrote Invisible: Stories from Kenya’s Queer Community, in which you carried interviews with members of the LGBTQ+ community in the country. What surprised or did not surprise you about the stories you documented?

That feels so long ago, but I loved the fact that the stories felt very kawaida and that is what I wanted the book to achieve, and it did. The stories in the book were relatable. I was impressed by how many of the contributors, in spite of the terrible things that were done to them, stood up for their truth. I have a lot of admiration for them.

I wanted to collate stories from different parts of the country. Those interviews were emotional and I was really surprised by the desire many of the contributors had to get their stories out. It felt like they had been bottling up this aspect of their lives for years. My journey was a walk in the park compared to what some of them went through. But I am grateful that they trusted me with their stories. There was lots of laughter, shock, tears and tonnes of respect and admiration in putting Invisible together.

Q. You air a podcast called Nipe Story. Tell me a bit about it and why you founded it.

Nipe Story is a storytelling podcast that produces audio versions of short story African fiction. It started in December 2017. I love African literature, the spoken word and long form audio. I’m a trained radio producer. I love manipulating sound and love doing voice-overs and the podcast was an opportunity to do all those things. It showcases literary work from novice and experienced African writers. It was also important to have a platform for queer fiction writers. At that time, I don’t think there was a platform through which you could access queer fiction digitally and I’m proud of the fact that I have created a space for that.

I wanted Nipe Story to be a platform that celebrated all sorts of African writers and fictional writing and more so orally. It has been a labour of love and the podcast has added so much to me even as a writer and audio editor. I consider it a master class of short form African fiction. You get to hear different styles of storytelling, themes and expressions, plus you get to ‘travel’ the continent. I’m really glad to have created a platform that celebrates African writing and grateful that many writers have entrusted me with their work. I also want to display the variety of voices and expose the voice talent that is available.

Q. A few years ago, you were diagnosed with multiple myeloma for which you got treated in India. Most people I have spoken to who had or have cancer say it is a life-changing moment, both in a positive and negative way. How did cancer change your life?

It will be eight years in October since my diagnosis. I relapsed last year in April and have just concluded treatment. I keep saying that cancer gave me a voice. Most people who have had a cancer diagnosis note that the disease gives them a whole new perspective on life and on their person.

Since October 2015, I have learned a lot about myself. It’s like the disease released a Kevin who had been suppressed for 42 years. Now, no more people-pleasing and I’m thinking about what I was put on this earth for. I always tell people that we only have this life. This is all I know. I started living in spite of chemotherapy, a transplant and a battery of side effects. I embraced who I was.

Furthermore, I have learned so much about how to navigate life in a way that agrees with me and how best to live with other people. I’ve also learned to protect myself from things and folks that could hurt me and my mental well-being. I avoid stressful situations because my body isn’t what it used to be. I’ve been listening to my body even more keenly since I got diagnosed. My body is also different; it’s not just middle-aged, but also more vulnerable but also stronger. I’m exercising my mind, body and soul. Those three have also become stronger and my heart has grown. It is terribly bruised but it has grown stronger and bigger and is fuller.

I love spending my time in nature. We have a beautiful planet and I’m privileged to take in its beauty in the stage that is Kenya. I work better and I was given the opportunity to tap into the things that make Kevo, Kevo. My essence. I took the pen a lot more seriously when I got diagnosed and look at me now. Cancer birthed a storyteller and I’d been sitting on this gift – a gift that I’ve been able to share with so many people. I knew I was creative but I didn’t appreciative how creative I was.

Battling cancer is indeed a mind-over-matter strategy, but also it’s going through this journey holistically and realistically. There are days and moments that I don’t have the bandwidth to offer emotional support to others because I am also struggling and in a dark hole with nothing to give. It gives you resolve but it also tests you to the core. It is persistent, ruthless, annoying, frustrating and a humbling disease. I’ve cried so many times because I just wanted a side-effect to stop. It knocks you down but you have to dig deep so that you can stand up. And when I was done, I’d hope I’d have it within me to get back up. That’s where the mind kicks in. There were times I don’t know how I made it through the storm but I did.

And I’m grateful for that.

This journey is tough emotionally, because people still die from the disease or undergo harrowing experiences and there is nothing that you can do to change their situation. I’ve learned acceptance but it also comes with grace and the ability to release and respect each one’s journey with the disease.

I’ve learnt to be careful with my words and also ask what form of support needs to be offered to other fighters. And I’ve had to ask myself whether I’m ready or strong enough to offer my shoulder. There is a close friend of mine who when we meet we have milkshakes, laugh and talk sh*t and then we hug and go on our way. And then there are days when we want to vent about how frustrating the dawas are or how hard the journey is. Sometimes just telling someone that I am thinking of them is all that is needed.

I’ve learnt to live in moments.

Moment by moment because a day on a really bad day is too long to get through. I am doing my level best to live in the now. To stop and rest and to be a good human. I’m trying to ensure that I am carrying what is really necessary for this journey, and I am ensuring that I am living my best life. I want to go through the rest of my days living my authentic life. Living that way has made me embrace and appreciate my sexuality even more and forced me to do a lot of internal work, like forgiving myself, giving thanks and, as cliché as it may be, loving myself more. Cancer forced me to start seeing me and to start valuing who I am and loving that person who for many years I’d neglected. Plus, there’s a lot more gratitude in me.

Q. I find that like HIV, there is a lot of stigma and fear around cancer. Friends and family disappear from your life, thinking perhaps that the disease is contagious. Then other people you never expected come forward to give you hope and inspiration. Was that your experience?

I am still baffled at how much kindness I received from all quarters. From home and away. I struggled with that initially and I remember my therapist telling me to be open to kindness. That changed me, though there are still moments I struggle with receiving kindness. I’m the guy who is usually the giver not recipient of kindness. I got humbled and realised that there is nothing wrong in asking for help or receiving help. It was selfish of me to deny them the joy of being a giver of kindness.

People have come and gone not because of the cancer but because we are at different stages in life. I’m a lot more protective of my space and things around me. There is no room for the banal, the selfish, the hateful, the unkind and the disrespectful. Those aspects take too much energy. Why bother being in such spaces or around people who choose to live like that? I’m learning to draw boundaries and protect those boundaries, so that even when I encounter individuals like that I have protected myself and will be true to myself.

I also recognise that I made the decision to move from Nairobi to Kilifi because I wanted to be in a space that was good for my mind, body and soul. I wanted to heal and I knew being in Nairobi was not going to make me better. Being here was also good for my creativity and spirituality. So, along the way, I have met several like-minded folks who are honest enough to admit their own struggles, celebrate their triumphs and are comfortable in their skin. I’m focusing on that and not who walked away. Be open to the surprises in life. There is a lot more kindness out there in the world. It needs to be shared.

Q. Cancer patients also talk about the dark, ugly and highly exploitative medical treatment for cancer in Kenya that is in cahoots with Big Pharma. A lot of cancer research on alternative cures for cancer is presumably suppressed, which means patients are not offered other options besides surgery and chemotherapy. What has been your experience?

We can talk about the bad but we can also talk about how people are getting healed and cancers are being spotted early. I recognise our healthcare system is far from great but there is a greater awareness of the disease and there is a lot more openness. Yes, we must call out the flaws that exist, but we need to be objective.

We live in a society I believe is over-medicated. We run to get antibiotics for everything without giving our bodies the chance to fight for itself. I know when I get a flu it now takes me not five but at least seven days for it to pass. I rest, sleep, eat well and have lots of fluids. Yet, we also live in a society where we don’t question doctors, or rather, don’t engage or build relationships with doctors or medical personnel. Both parties need to see one another as human. That, I believe, is important in the healing process. I think we also have to be empowered to say I am drawing a boundary on what is going to go into my body. My body, my choice. Speak for your body.

I can’t describe that medical treatment the way you have in your questions. There are elements that I disagree with in the system but I recognise that there have been advancements in cancer treatment that need to be applauded. Look at the HPV vaccine. Here is an opportunity to prevent cervical cancer, and with fewer cases of that, resources can be channeled to other diseases.

In the last few years, we have seen a better understanding of myeloma and doctors are now able to diagnose it earlier. We are seeing more medical students studying oncology in Kenya, clinical trials are being done in Kenya and we have PET scan machines in the country now for those who don’t want to travel abroad. Folks from the region are coming to Kenya and not just Nairobi for treatment. Look at what is happening in Eldoret, at Moi Referral Hospital? Patients don’t just have to be ferried to Nairobi any more.

I’ve just undergone treatment for a year and two months here at the Coast. Sadly, we still don’t have that many oncologists and hematologists based out of Nairobi, but things have changed. We still need more oncologists, facilities and oncological nurses.

However, we need to see prices of medicines and treatment come down. NHIF [National Hospital Insurance Fund] has helped but we still need to find a way to make cancer treatment less expensive.

It is an expensive disease globally and we need to encourage the use of complementary forms of treatment outside of conventional methods. Patients are not being told about alternatives to dealing with pain, for instance. We need to be talking about medicinal marijuana and making it legal and accessible for those who don’t want to be on morphine or other opioids.

We need practitioners who offer non-conventional forms of treatment to be listened to and offered a seat at the table when we are discussing the national cancer strategy. I was at the first cancer summit in the country in February and there was no presence of alternative practitioners. No one was talking about lifestyle changes as a preventative measure.

As cancer patients, there is already enough toxic material going into our bodies; patients want to endure their treatment with dignity and we need to have that as part of a wider conversation. We need to champion options for patient treatment and patient care. This thing of one-size-fits-all doesn’t work. It amplifies the beast of cancer and reinforces fear of the disease. Nip this disease in the bud early even before you get to hospital.

We need to know more about how to minimise chances of getting cancer through exercise, diet, stress management, having more green spaces and having conversation on mental health. Are we living in cities that allow for healthy living? Is our air clean? What is going into our food? What should we be eating?

This approach will empower individuals such that if they do get diagnosed with cancer their minds and body are in a much better shape to combat the disease. We’d see early detection, fewer deaths and better longevity and quality of life of patients living with cancer and even other chronic diseases. A more patient/human-centric approach is needed.

We need better policing and monitoring of the organisations that are importing cancer medicines into the country. Sadly, the charlatans are already cashing in on this. I discovered this last year when I was looking for my own medicine. The variance in prices of the same drug was astronomical! I had to ask myself how that could be right. People, sadly, see cancer patients as an opportunity to make lots of money. Buy your drugs from a registered pharmacist not just any Tom, Dick and Harry who can get you a good deal.

The other conversation that needs to be heard is with the health insurers and pushing them to consider waiting times and the cost of cover for not just cancer patients but patients with chronic conditions. A waiting time of a year before a policy kicks in doesn’t help.

There are brilliant, kind and thoughtful doctors and nurses out there caring for patients but we also must be careful on how much rope is being given to Big Pharma in accessing institutions that offer medical care. There needs to be a way of protecting the patient, not protecting the profit. We all end up being patients in some shape or form. We really must have more thoughtful, honest, innovative, inventive and humane ways of dealing with cancer in the country.

Author

-

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist with over two decades of experience as an editor, writer and communications specialist. She wrote a weekly op-ed column for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, for many years, and has contributed to various regional and international publications, including, the UK’s Guardian, Africa is a Country, The East African, The Mail and Guardian, The Elephant, and Kwani? She has worked as an editor and writer at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and has published two books on Somalia: Mogadishu Then and Now (2012) and War Crimes (2016). Her first book, Triple Heritage (1998), explored the history of South Asians in East Africa. Her latest book, Lords of Impunity (2022), examines the failures and internal contradictions of the United Nations and what can be done to transform this global body. She holds a Master’s degree in Communication for Development from Malmö University in Sweden and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and Women’s Studies from Suffolk University in Boston, USA. She is based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist with over two decades of experience as an editor, writer and communications specialist. She wrote a weekly op-ed column for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, for many years, and has contributed to various regional and international publications, including, the UK’s Guardian, Africa is a Country, The East African, The Mail and Guardian, The Elephant, and Kwani? She has worked as an editor and writer at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and has published two books on Somalia: Mogadishu Then and Now (2012) and War Crimes (2016). Her first book, Triple Heritage (1998), explored the history of South Asians in East Africa. Her latest book, Lords of Impunity (2022), examines the failures and internal contradictions of the United Nations and what can be done to transform this global body. She holds a Master’s degree in Communication for Development from Malmö University in Sweden and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and Women’s Studies from Suffolk University in Boston, USA. She is based in Nairobi, Kenya.