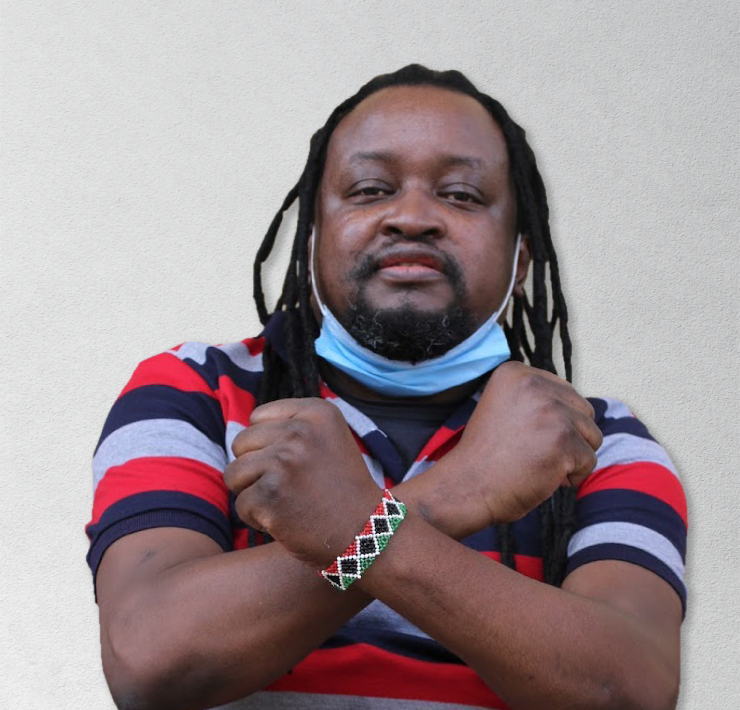

After a long career in teaching law at the University of Nairobi, Dr. WILLY MUTUNGA was detained without trial in July 1982 by the Daniel arap Moi regime for fighting for democratisation. He went on to head the Kenya Human Rights Commission, which he co-founded, and served as the president of the Law Society of Kenya. After decades of fighting for the rights of Kenyans, he was appointed as Chief Justice and President of the Supreme Court of Kenya in 2011. RASNA WARAH spoke to the eminent human rights activist and scholar about his illustrious career, and why the struggle for equality and justice in Kenya has been so difficult.

Q.You have been out of the limelight since you retired as Chief Justice in 2016. What have you been up to lately?

I have been consulting, teaching, writing, and working with social movements run by young people. I have also kept contact with former civil society colleagues in human rights and social justice movements. I have kept contact with comrades I have all over the globe.

Q.You were the first Chief Justice to be appointed after the promulgation of the new constitution in 2010. As Chief Justice and President of the Supreme Court, you introduced far-reaching reforms in the Judiciary, including establishing courts in remote parts of the country, and ensuring that courts had clean, functioning toilets. Of all the reforms you introduced, which one are you the proudest of?

The integration of African Justice Systems (AJS) with colonial and postcolonial justice systems. Thus, I am very proud of starting a journey of justice for all Kenyans and breathing life into Article 159 (2) (c) and (3) of the constitution on alternative forms of dispute resolution, including traditional ones, as long as they do not contravene the Bill of Rights. The journey I started has been continued by my two successors, CJs David Maraga and Martha Koome.

Q.You have been a vocal advocate for women’s rights, but have admitted that becoming a feminist was a tough journey. You have stated, “Men should be feminists, even if it is hard work.” Can you elaborate on what you meant by this?

I meant that men are not socialised to be feminists. Those who want to be feminists have to realise it is a struggle with many hurdles, and ultimately, you will be glorified and vilified in equal measure. The struggle could result in one being a better human being who respects the dignity of all human beings, women, in particular.

Q.Many Kenyans, including me, were angered by the Supreme Court decision declaring the 2013 election “free and fair”. As President of the Supreme Court, you defended this decision. However, it polarised the nation even further and led to significant voter apathy in subsequent elections. Does that ruling weigh on you sometimes?

What weighs on me is the impossibility of delivering a decision that will be accepted by all. We live in politics of division, which means that half of the country will be happy while the other half will hate the decision. What is mitigating for me is this realisation, the fact that our politics is ethnicised and monetised, and those who come to the Supreme Court – petitioners and their adversaries – come to the Supreme Court with dirty hands and they and their supporters should be the last to complain about decisions made by the Court of Equity. Finally, it bothers me when the decision is individualised. Six of us decided. Kenya is forever polarised and voter apathy cannot solely be blamed on a Supreme Court decision. I doubt if there’s data that can confirm and validate that assertion.

Q.What has being an activist and fighting for the downtrodden taught you about Kenyan society?

It has taught me that Kenya is ruled by neocolonials (invariably called compradors, barons, or simply the elite) who are agents of foreign interests and not of national interests. Activism has taught me about links and continuities of our struggle for land, resources, and freedom that I have made part of my life. Activism has given me a vision of a planet I would like to see – a socialist one.

Q.What future do you see for Kenya?

A Kenya with great political opportunities to create an alternative political leadership that is anti-imperialist, and anti-comprador, one that fights both interests in the name and interest of the people of Kenya, and the downtrodden in Africa and the rest of the world. I do not see any alternative to this future for our country except if we agree to support the status quo of poverty, exploitation, death, corruption, oppression, and foreign domination.

Author

-

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist with over two decades of experience as an editor, writer and communications specialist. She wrote a weekly op-ed column for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, for many years, and has contributed to various regional and international publications, including, the UK’s Guardian, Africa is a Country, The East African, The Mail and Guardian, The Elephant, and Kwani? She has worked as an editor and writer at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and has published two books on Somalia: Mogadishu Then and Now (2012) and War Crimes (2016). Her first book, Triple Heritage (1998), explored the history of South Asians in East Africa. Her latest book, Lords of Impunity (2022), examines the failures and internal contradictions of the United Nations and what can be done to transform this global body. She holds a Master’s degree in Communication for Development from Malmö University in Sweden and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and Women’s Studies from Suffolk University in Boston, USA. She is based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan writer and journalist with over two decades of experience as an editor, writer and communications specialist. She wrote a weekly op-ed column for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, for many years, and has contributed to various regional and international publications, including, the UK’s Guardian, Africa is a Country, The East African, The Mail and Guardian, The Elephant, and Kwani? She has worked as an editor and writer at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and has published two books on Somalia: Mogadishu Then and Now (2012) and War Crimes (2016). Her first book, Triple Heritage (1998), explored the history of South Asians in East Africa. Her latest book, Lords of Impunity (2022), examines the failures and internal contradictions of the United Nations and what can be done to transform this global body. She holds a Master’s degree in Communication for Development from Malmö University in Sweden and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology and Women’s Studies from Suffolk University in Boston, USA. She is based in Nairobi, Kenya.