My first ever interaction with cervical cancer was through a study happening at the Kenyatta National Hospital that was researching the possibility of cures for early stages of cervical cancer. At the time, I was an 18-year-old high school graduate employed to collect basic data, but beyond just the requirements of the job, I really wanted to understand Human Papillomavirus and what it does to our bodies, especially female bodies.

Part of my brief in the study was to ask select women some really uncomfortable questions that I don’t think they would have answered if they knew my actual age. Either way, I put on a brave face and got down to work, the white lab coat really helped when it came to asking how many sexual partners each of the women had, for instance. It is through this exposure of working at Clinic 66 and Clinic 18 – two women clinics at Kenya’s (if not East Africa’s) largest referral hospital – that really fueled my ambition to become a gynecologist at the time, before the realities of medical school hit me hard and set me straight – like the expectation to face a cadaver for an entire year studying human anatomy.

But back to my 18-year-old aspiring gyna-self.

As I sat there brave-faced with pen-and-paper, I interacted with women who only came to the clinics for their annual pap smear, with some getting the shock of their lives two weeks after undergoing the process for the first time ever by learning that they had abnormal cells in their cervix.

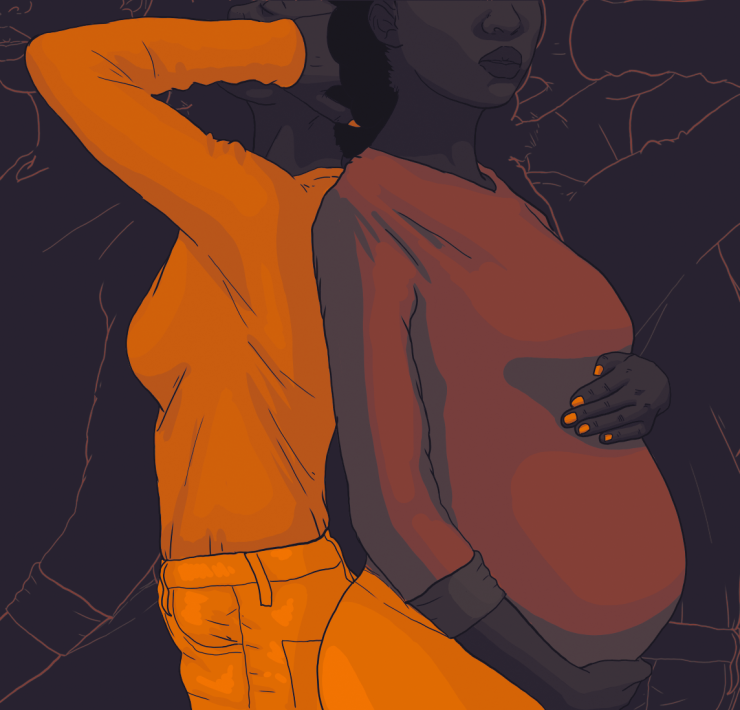

It was as I was taking in all of these shockers and potential life altering realities that I came to the hurtful realization that cervical cancer doesn’t choose an age – and not that any age bracket deserves this. Most heartbreaking for me was the case of Vienna*, a 25 year old lady who had been married for two years and had had three sexual partners prior to her marriage – and had never conceived before – but upon doing her first pap smear ever found she had abnormal cells in her cervix.

For Vienna, the most natural thing to do was to do a biopsy and determine a treatment plan. After six months with no change in her condition, doctors advised Vienna to do a hysterectomy – a surgical procedure to remove the womb. Much as the treatment was life saving, this series of events broke my heart, but at the same time made me even more curious as to how cervical cancer affects families, since I watched as Geneve*, Vienna’s new husband, expressed as much worry for her wellbeing as she did for herself, both wanting to know what the future portends for their nascent family of two.

Cervical Cancer in Numbers

Going by Vienna’s and Geneve’s, it goes without saying that this particular silent but deadly cancer – like all cancers in a way – poses a threat to families, marriages and the communities we dwell in, more so in low- and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization reported in 2018 that every two minutes a woman dies of this preventable cancer, affecting typically younger age groups as a result of early or multiple sexual partners. In the 17th World Congress for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy Dr. Harsh Vardhan, at the time India’s Minister of Health, Family and Welfare, stated that each year 250,000 female deaths in his country are attributed to cervical cancer. As always, the figures may even be higher considering the challenges in access to health care and deficiencies in health information systems and cancer registrations in developing countries especially in Asia and Africa (a continent in which this preventable but most common cancer accounts for 22% of all female cancers diagnosed each year.)

Bringing it back closer home, the health reporting site Afya Watch submits that cervical cancer kills nine women in Kenya daily, making us rank among the top 20 countries with the highest rates of cervical cancer in women of reproductive age. Similarly, Kenya is found to have the highest cervical cancer-related deaths across East Africa, with estimates from the Stop Cervical Cancer organization showing that the number will double to 22 deaths per day by 2040. These are the deaths of women who are working, raising children, caring for families and contributing to the socio-economic fabric.

The Virus

The cervical cancer-causing Human Papillomavirus, otherwise known as HPV, has been known to be very common in both men and women. In fact, according to the Center for Disease and Control (CDC) most people who are infected with HPV don’t usually know they are infected. In some cases, the person’s immune system gets rid of the infection within a two year period. Research shows that by age 50, at least four out of every five women will be infected with HPV at one point or another. Furthermore, men, more often than not, have no symptoms and end up being carriers of the virus.

The obvious solution to dealing with HPV would be to promote early detection through frequent pap smears, which have been made affordable and accessible. Over time, health facilities have made it a habit to carry out medical camps and campaigns in a bid to increase cervical cancer screening, efforts which have seen the number of women conducting pap smears increase across the country.

The Hindrances

Sadly, there are sex (biological) and gender (socio-cultural) aspects to the practice of medicine in this part of the world, and the treatment (and early detection) of this cancer proves to be no different. Research published in the International Journal for Equity in Health titled “Applying a gender lens on Human Papillomavirus Infection; Cervical cancer, screening, HPV DNA testing and HPV vaccination” highlighted that access to these free and frequent medical camps and drives may not be free and fair to all.

The study shows that women categorized as less educated, older, uninsured, homeless and migrant face more barriers, with women who have sex with other women and obese women participating less frequently in pap smears. The study further explores cancer from an intersectionality approach, addressing the way gender and other social identities and forces interact and relate with each other in order to give shape to the mosaic of human experiences – a lot of time to women folk’s disadvantage.

In fact, the absurd reality about this particular gendered cancer which is preventable is that even the ability of more women from developing countries to participate in such studies remains curtailed by socio-economic forces within communities.

The Vaccine, and A Ray of Hope

Luckily, the discovery of the link between HPV and cervical cancer birthed the possibility of immunization, with the vaccine becoming one of the primary prevention efforts of cervical cancer. However, it is the early intervention strategy by governments of targeting the virus in 10-15 year old girls that has stirred controversy. This has meant that part of the public health advocacy campaigns need to target parents and guardians who have 10–15-year-old girls, and this has paused a challenge. Instead the remedy recommended by opposers of the vaccine is a behavior change campaign among teenagers and young adults to reinforce abstinence and yearly cervical check ups to detect the vaccine before it’s too late.

Understanding African family and religious set ups, I am certain this would not fly in many African homes because of the avoidance of thinking of young girls as sexual beings, yet a lot of sexual violence victims report that most of their abusers are relatives or people they have interacted with-Ironic.

In a debate show on Citizen TV, Dr. Collins Tabu, Head of National Immunization Program explained the rationale around the choice of targeting, mentioning that the vaccine is a preventive measure to the sexually transmitted virus – and not the cancer – and thus the need to target girls and boys early before they get into contact with this sexually transmitted virus. Just as certain baby vaccines work optimally at certain ages – for instance BCG for newborns – the HPV vaccine works better for 10-15-year-olds – ideally before they become sexually active.

In the same interview, Dr. Jane Githinji, also known as Daktari wa Mtaa, mentions a study done by the Kenya Demographic and Health survey that highlighted 15% of of teenagers start having sex by the age of 15, with 50% having already engaged in sex by the time they are 18 and 71% by age 20, hastening to say that, “Vitu kwa ground ni tofauti” – the numbers could be more thus the need to vaccinate early.

Will Science Prevail?

As is now commonplace, with every debate about life choices, religion has come to play a role on how individuals make decisions. For some, the general concern is around the side effects and safety of the vaccine, but for the faith-based skeptics, the vaccine is considered as an indirect endorsement of promiscuity. In an article published by Catholic Philly titled Amid Church Concerns, Kenya Rolls Out Vaccine Against Cervical Cancer, a Kenyan parent shared her comments around the HPV vaccine stating that it may even end up giving its recipients cancer, with Archbishop Kivuva Musonde of Mombasa Diocese stating that the government should not accept vaccines from abroad without ascertaining its safety as Africans might end up being guinea pigs.

Unfortunately, the anti-vaxxers movement is real.

The Need for Continuous Education

It is thus self-evident that before administering the HPV vaccine, health conversations need to happen across society, especially among teenagers, parents and doctors. There must be a clear and concise information pathway to community leaders and other stakeholders addressing specific content concerns, for them to understand that the vaccine is against the virus and not against cancer, since the only way to reduce the numbers from the nine women who die out of cervical cancer everyday is by understanding the need to curtail the Human Papillomavirus. Education and policy making around pap smears while taking into consideration socio-economic factors that come to play in health equity will similarly increase participation of pap smear medical camps.

Further, efforts to educate the entire family unit – men, women and children – must be put in place in order to push for health equity and improve accessibility of health facilities – so that men can support their wives and daughters towards (prevention and treatment) of this cancer. It is a right for both men and women in the country to have health access, since limiting them based on socio-economic power is a violation against the inherent right to accessible and affordable healthcare. Granted, achieving sexual and reproductive health rights is a gateway to a healthier, freer society.

*Names have been changed to hide the patient’s identity.