Nurses. They are often left to linger in the shadows of doctors. They have been, and still are, some of the unsung heroes in the global healthcare ecosystem. Yet, because of the common perception that physicians are the sole champions of healthcare, the deserving appreciation for nurses often takes a back seat.

To understand the importance of nurses, one must go back in time and look at the journey of nursing. In this case, how nursing became an occupation in Kenya.

How Nursing Started in Kenya

In East Africa, the first health centres were established within Christian mission stations during the colonial period. Before that, the community knowledge of diseases and their various treatments was orally passed down through generations, from father to son.

At the dawn of the 20th century, missionaries introduced Western medication to Kenya (then part of the East Africa Protectorate), with the big plan being to build hospitals and educate Africans about different diseases. This was to be done in order to reframe indigenous Kenyans’ attitudes towards various ailments, and to demystify Western medicine which was shrouded in superstition.

The first hospital was thus built in Weithaga in modern day Murang’a County in 1903. By 1910, there were three more hospitals within other mission stations – the Hunter Memorial Hospital (later known as the Kikuyu Hospital before a name change to its current name, PCEA Kikuyu Hospital ), the Maseno Mission Hospital, and the Tumutumu Hospital in Nyeri.

However, the introduction of Western medicine wasn’t received with open arms. In fact, in the beginning, because Western medical practice was seen as an infringement on African ways, it was almost impossible to get Kenyans to train on nursing and dressing. Most people didn’t want to be involved lest they be shunned by their communities.

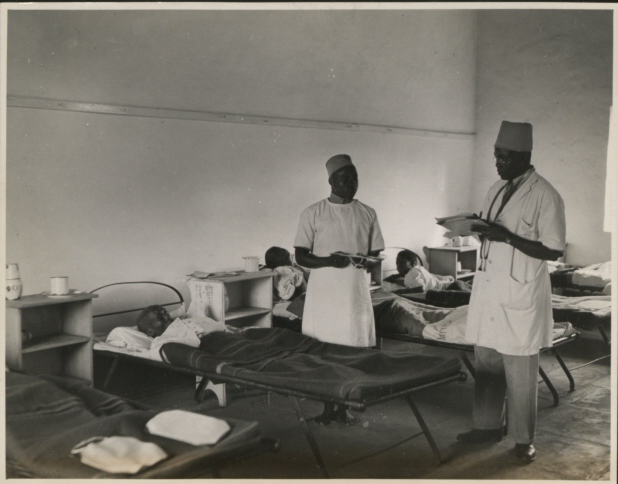

Back then, gender roles were clearly defined, and men were the sole decision makers in households. This meant it was men who were often approached by missionaries and encouraged to seek at the hospitals. Later on, these same men were persuaded to train as dressers. Slowly, the positive outcomes of hospital treatment were seen, and with time, attitudes were altered.

It therefore came as no surprise that because of gender roles and cultural norms, it was easier to access men, who in turn became the predominant gender to be trained as dressers in hospitals. The training usually lasted 3 years and covered cleanliness, sanitation, taking temperatures, dressing wounds and ulcers, and assisting missionaries with the hospital administration.

Then came the demand for Nurses

As more Africans visited hospitals and recuperated, and as populations grew coupled with the onset of the First World War (1914 – 1918), there was an increase in demand for Western medicine, and an even greater demand for medical personnel.

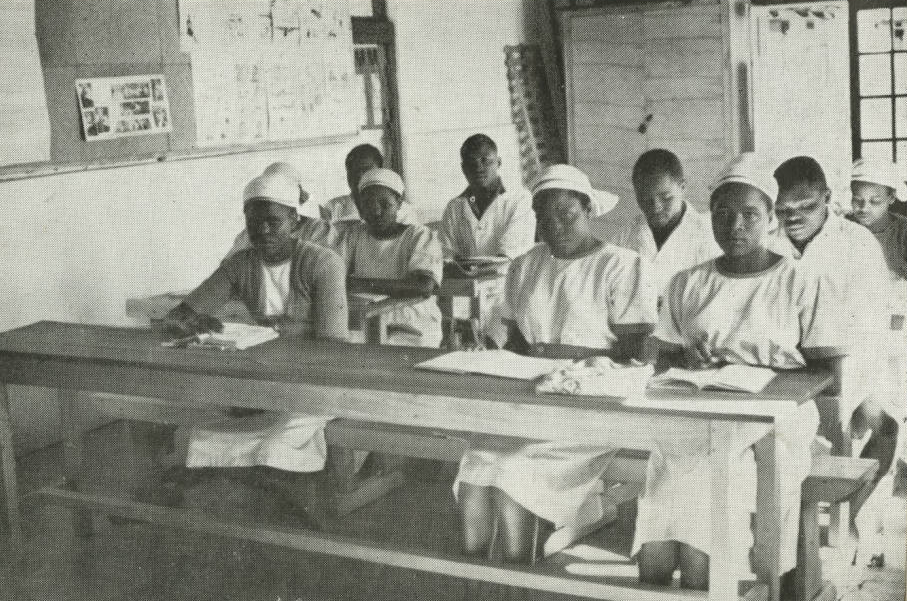

Therefore in 1929, the colonial government started training medical assistants. However, there was no formal framework in both the training conducted by the missionaries and that by the government. But then following the Second World War (1939 – 1945), the colonial government decided to standardize training of nurses. By the end of the 1940s, the Nurses and Midwives Registration Ordinance was born, such that the training of nurses was centered on the Nursing and Midwives Council of Kenya. As opposed to on-the-job training, nurses would now undergo formal training before they started working.

The first cohort of registered nurses in Kenya started their training in 1952. Three years later, in 1955, enrolled Psychiatric nurses started their training at Mathari Hospital (founded in 1910 as a smallpox isolation centre before it was converted into a psychiatric asylum).

In 1966, because there was great demand for personnel, the Nyanza School of Nursing started training community nurses – nurses who would have multi-purpose roles which ranged from working as nurses, midwives and as health visitors. And then in 1972 began the training for public health registered nurses in Nairobi. By this time, a Kenyan woman named Annette Kemoli had achieved the distinction of becoming the first Kenyan woman with a nursing degree.

A well-earned Nursing Degree

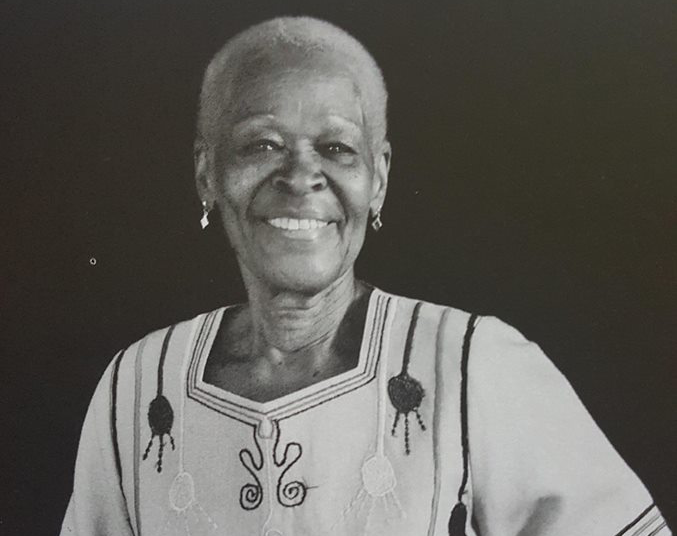

While it isn’t clear when exactly Kenyan women started training as nurses, Annette’s story is one of few that has been recorded and widely shared because of her achievements and her ability to withstand racism and the humiliation that came with it when she studied in the United Kingdom.

She had begun her nursing training at King George VI Hospital (present day Kenyatta National Hospital) and was one of two nurses selected to go to the UK to study an Advanced Diploma in Nursing and Midwifery. In 1963, she was back in Kenya to deploy her skills, working as a staff nurse at the same hospital where she had first trained, before transitioning to Chief Nursing Officer at the Nairobi City Council. Annette was later sponsored by the Council to enroll at McGill University in Canada where she obtained a nursing degree.

To sum it up…

By knowing the history of nursing comes the understanding of the importance of this occupation even today. Nurses are the cornerstone of the healthcare ecosystem. They are often the first to attend to patients, and in comparison to physicians, nurses spend a lot more time tending to the sick, and at the core of their job function is care.