The 2022 general election has come and gone, and with it the fierce competition that elicited rising political tensions that reverberated across the country. The outcomes were fiercely contested, with William Ruto’s presidential win being disputed by his main rival Raila Odinga, who for a third consecutive time lost the election by razor-thin margins. The petition process did not disappoint with the drama; there were nursery rhymes, poems and Victorian quotes at play. The curtain closed with more – hot air, wild goose chase, red herring.

Modern observation of electoral processes – not just the action on election day – has evolved since the days of the simple pen and notebook, with the Observer taking a strategic position inside the polling station to record any flaws in the exercise. Today, the Observer employs a more long-term approach to their assignment, aided by systemized methodologies and technologically-driven tools. A level of professionalism is also demanded in the process, but that’s a story for someday soon. At the end of the day, and despite whatever methods and tools, it is the contents of an Observer’s Diaries that tell an election’s ultimate tale.

Allow me to give you an exclusive sneak preview of my 2022 Election Observer’s Diary.

1. The Murky Preliminaries

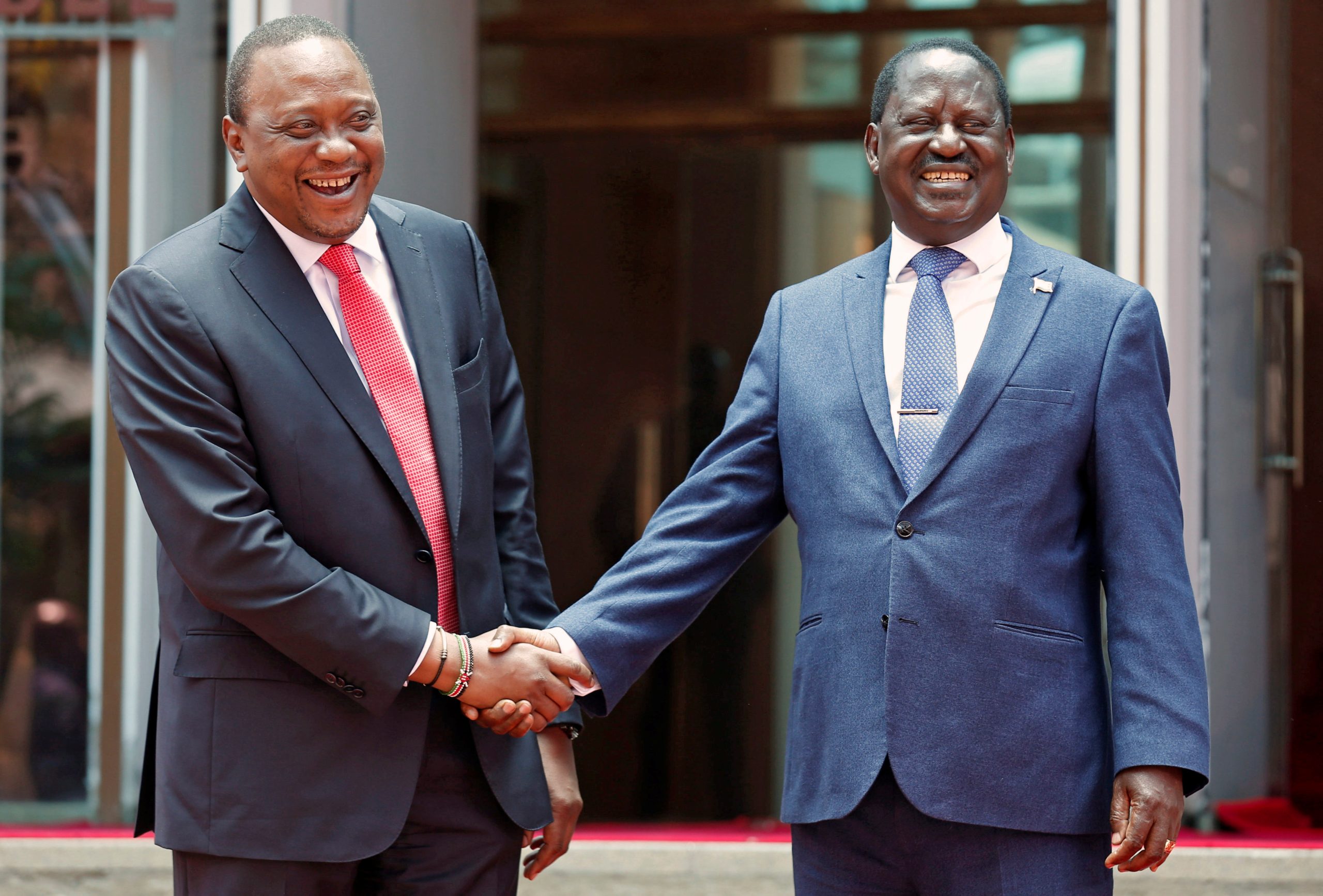

The script started immediately after the 2017 general election. Just a reminder of the resume then; hotly contested election between Raila Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta; Uhuru’s clear win (over 50% + 1) historically nullified by the Supreme Court after a successful election petition; a second election held on the 26 October 2017 boycotted by the opposition; Uhuru Kenyatta wins with about 38% of the total vote (well, simple majority is what was required for a win anyway); legitimacy of the elected government weighs heavily on the political scene leading to a very famous handshake between the two protagonists.

Things never settled since then. Embarking on one of the longest and illegal election campaigns (the Observer noted this and publicly protested to the election management body, but no action was taken), the would-be protagonists Raila Odinga and William Ruto succeeded in putting the country in election mode since 2018. The shadow contests manifested themselves in attendant by-elections (remember the Kibra ‘Baba’s bedroom’ battle), political alignments and realignments and even the exploitation of incumbency privileges. By the time the official campaigns were announced on 29 May 2022, the country was spent. Endless rallies were held in every possible space. Apparently, thousands of people had been hired and rented to attend these popularity contests. At times, even where the numbers were not good, digital keyboard warriors did the trick to secure virtual crowds for television audiences to savor.

2. The Tale Tell Pre-Election

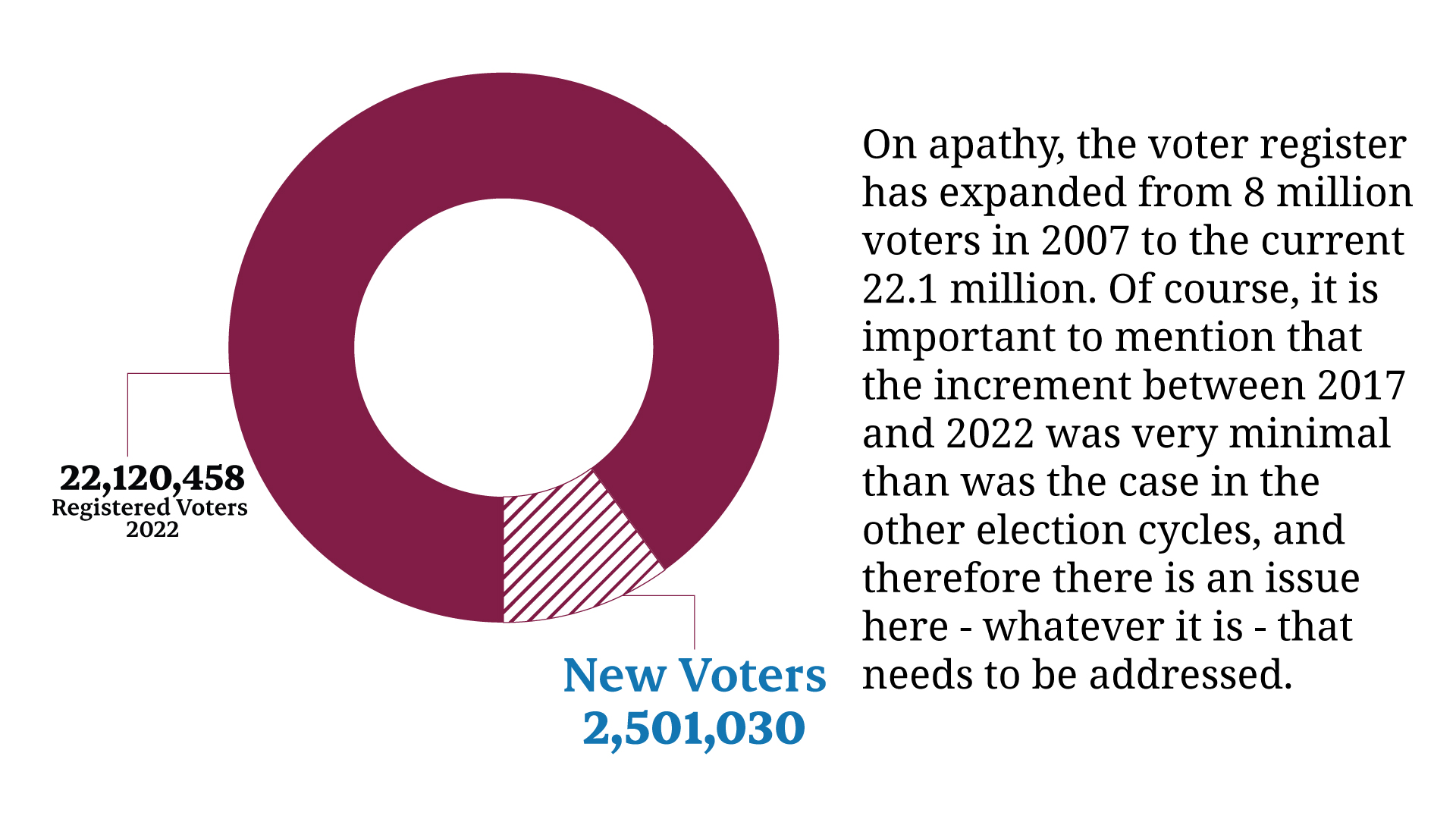

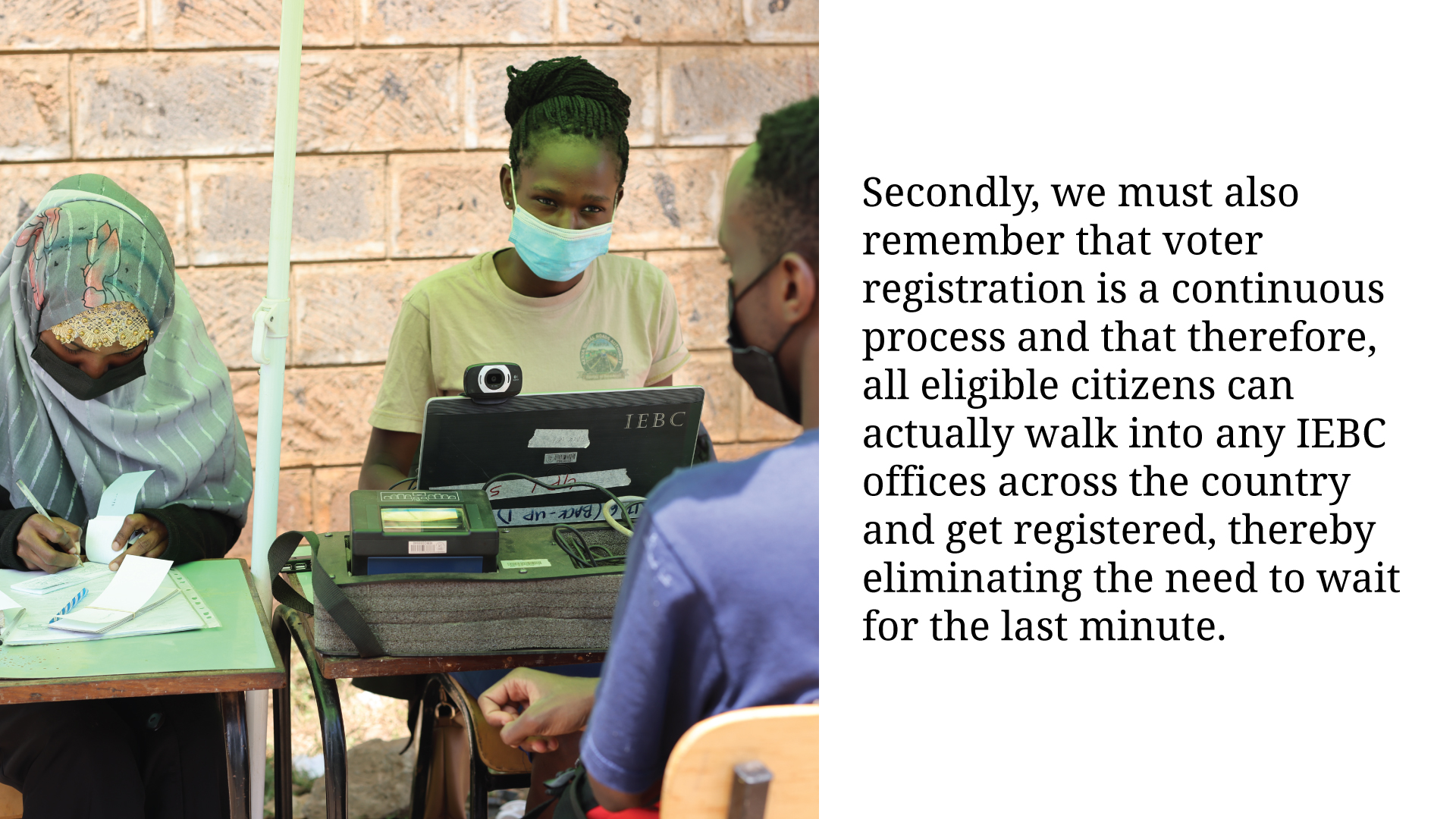

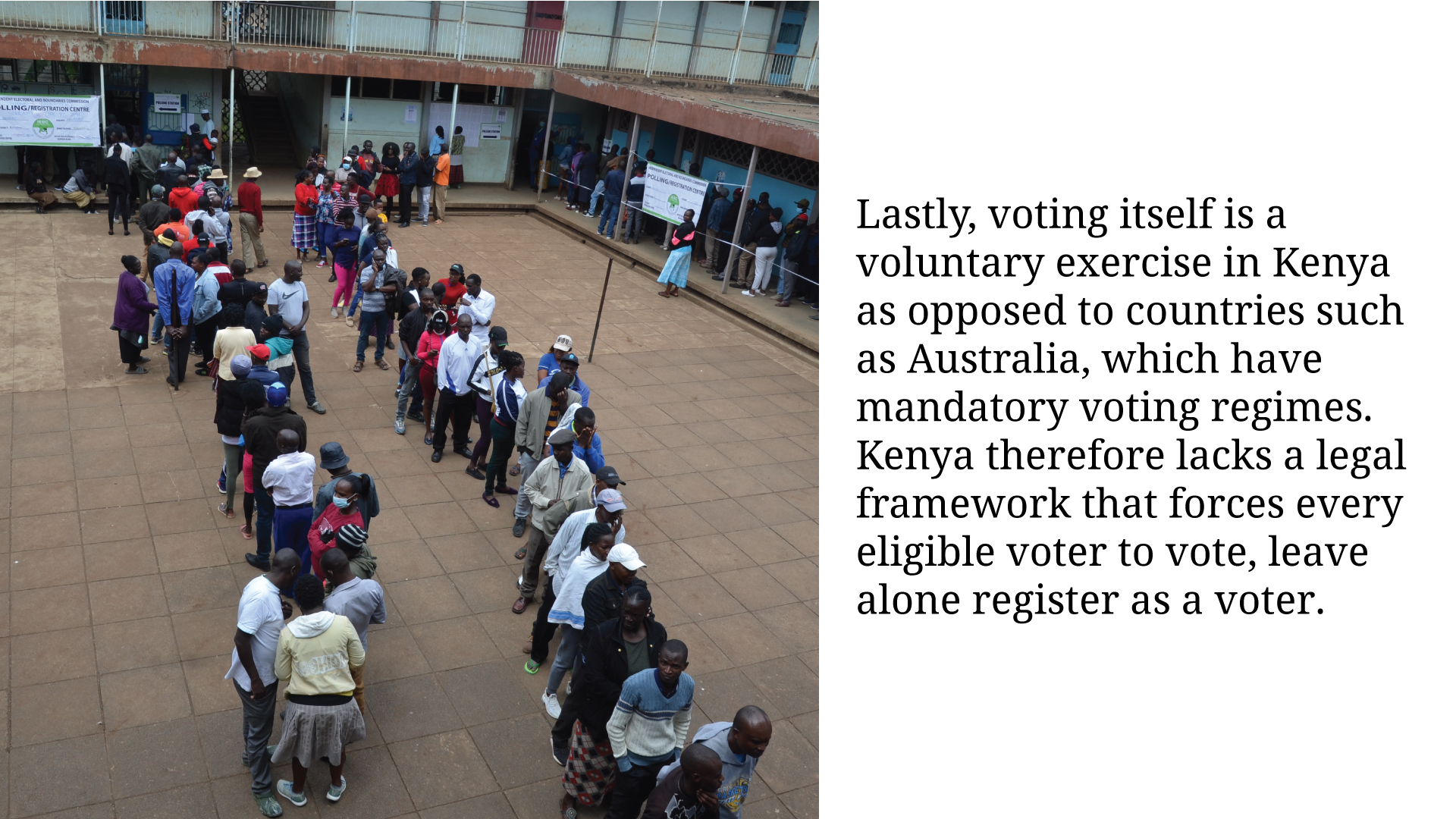

In the immediate pre-election period, the Observer’s Diary reveals a number of things, the first one being that the Election Management Body (EMB) needed to ensure it enfranchised as many new voters as possible. Every year, the National Registration Bureau (NRB) issues IDs (the trump card for voting eligibility) to more than a reported 1 million young people, the much sought after new-voter demographic. It is therefore estimated that at the very least, there would be 5 million new voters coming in every electoral cycle. Working with these estimates and official figures from the NRB, Kenya’s EMB, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) embarked on two mass voter registration campaigns targeting 6 million voters. The outcome was dismal, with IEBC only getting 25% of the target.

Now people argue voter apathy. They also argue a lack of a robust engagement by the IEBC especially in targeting the youth. Here, the Observer notes as follows:

So basically, even despite the onslaught of the long-running political campaigns and the heated political environment, the country’s new voting population was neither excited nor enticed. It was obvious that you can take a cow to the river, but you cannot force it to take the water. It later emerged that even for those new voters who did register to vote, their overall turnout on election day was less than it was in the last two elections, standing at 64.77% (2013 – 85%, 2017 – 79%). While these are still good numbers if compared across the globe, the Observer reckons that there is a clear message in these numbers: that something needs to be addressed quickly, before the younger generation becomes critically apathetic.

3. The Rickety Political Parties

The Observer’s Diary similarly references the goings-on within political parties pre-election. In 2017, political parties, the most viable vehicles for the acquisition of state power, held very shambolic nomination exercises. Many candidates and party members were disenfranchised through a host of fraudulent processes that were employed by each party. From illegal party registers; to whimsically moving polling stations; to missing ballot papers; to postponement of elections; to unregulated direct nominations and issuance of certificates to unpopular candidates, the process was fundamentally flawed. In a country where political backing has been ethnicized and regionalized, winning a party ticket from the dominant political party in one’s electoral area is a guarantee to an assured win in the main national elections.

However, the 2022 situation was a bit different, perhaps courtesy of the amendments to the Political Parties Act, resulting in a more organized and better managed process, bottlenecks notwithstanding. The new Act introduced a number of methods that political parties can use to nominate candidates. In sum, parties were given greater leverage on devising less complicated nomination mechanisms. However, despite this generous leeway, the Observer notes that the ultimate will of the people (party members in this case) was not adequately entrenched in the employed approaches. This area, therefore, is still a work in progress.

4. The Political Parties’ Matters Arising

At this juncture, allow me make a brief mention of some of the issues noted in the run-up to the election, some of which had a bearing on election outcomes later on.

5. The Ghosts and Angels of Technology

The Observer takes note of the infamous ‘Venezuelans Affair’ that would later characterize the presidential petitions after the declaration of results by IEBC. While the specific details of their engagement still remain scanty – the Observer isn’t privy to them – the Observer takes note of the critical question of Kenya’s sovereignty in the electoral process. While the issue of Jose Carmago and Co. was settled by theIEBC in respect to their professional engagement as support to the Commission’s technology infrastructure, the question that lingered on the Observer‘s mind was, had Kenya bitten more than it could chew as regards technology?

Since the advent of the robust use of technology in our election in 2013, different animals keep emerging. If it is not the procurement and associated cost ghosts, then it is the hacking of the system or opaqueness (yes that word again) of the transmission process. This time we even had overlays of the Jose Carmago ghost and other interferences as adduced in court, prompting the bench to term them ‘hot air and wild goose chase’, among other adjectives.

6. The Verdict On Technology

The Observer admits that whatever technology has been employed so far is yet to meet the Article 86 threshold of a simple, secure, verifiable, transparent and accountable system.

Even going by the weighted prominence of simplicity, should we have an election system that can only be operationalized using foreign support? Is that not selling ourselves short? Is that not compromising our sovereignty? And what are we to do with vendor locking which is brought about by commercial contracting? Is that not the pathway to not opening the servers? And lastly, associated with this, what leverage does an Election Management Body have over private entities whose services affect sensitive areas of an election such as results transmission? What guarantees are there to the Kenyan electorate that an election wouldn’t be compromised but such non-sovereign (or are they the realm sovereign) contractors? As Germany (a technology giant of reckon) did some time ago in their elections, perhaps we need to go slow on election related technology until we find the missing proverbial silver bullet(s), be they technology-enabled or technology-related or not. We need an answer.

7. The Commissioners’ Evolving Soap Opera

Then, of course, there is the reckoning within the IEBC, a body corporate.

When Commissioner Roselyne Akombe resigned dramatically in late 2017 fearing for her life, it was obvious to the country that something was amiss in the management of the IEBCs affairs. Later, three other Commissioners resigned in 2018 in a near-choreographed manner.Despite these vacancies, it took nearly 4 years to replace the four. It also took the same amount of time to confirm the new head of the secretariat after the resignation of Commission CEO Ezra Chiloba in 2018. The above twists created a discordant Commission that would later split right in the middle during the declaration of the 2022 election results.

The Observer notes that this state of affairs is not healthy for the management of elections in the country. A serious review of Kenya’s Election Management Body model needs to be undertaken. It is obvious that the main reason for the foregoing is interference from the political class which dilutes the independence of the agency. Perhaps, it is time to revisit the discussion on a political model where parties participate in the choice of the Commissioners.

8. Observing D-Day

So Election Day it is; 9 August 2022!

First the numbers. There were 22.1 million registered voters; 46,229 polling stations; over 400,000 polling officials; and just over 16,000 approved candidates vying for the six elective positions. At the presidential level, the race had four candidates, with two frontrunners going neck to neck according to various opinion polls.

And to salute my fellow observers, this particular Election Day witnessed an unprecedented high number of foreign observation missions, who brought with them an extra layer of international media attention as well.

As in the last two elections, all polling day operations went according to the script; the opening and set-up, the voting, the closing and counting. Even the KIEMs kits worked better (problems with only 6.1% as compared to 7.6% in 2017 and 54.5% in 2013).Granted, there were some challenges arising: late accreditation of observers and the press; anomalies in some of the strategic materials (ballot papers) leading to the postponement of two gubernatorial races and a few other elections; and flare ups of violence in some polling stations. All factors considered, the vote was more peaceful than previous elections.

9 . The Waiting Begins

The events that followed Election day were most eventful.

Growing up (the Observer won’t give up their age just yet) election results were always about Members of Parliament, specifically who had been upstaged and who was the new kid on the block, and so on. Not anymore.

Perhaps it was out of the lack of luster in the presidency (the incumbent usually went in unopposed anyway under the one party state), but today Kenyans wait up majorly for the presidential seat. However, the IEBC officials were first announcing results of Member of County Assembly (MCA), all 1450 of them, then the 290 Members of Parliament (with little surprises here and there), the gubernatorial, Senate and County Women Representative. To the Observer, there were some very close races, but almost all the losing candidates were gracious in defeat, some going on social media to thank voters for their consideration.

10. The Evening, and Morning After

However, the elephant in the room was the presidential race.

First, a serious surprise for everybody, observers included.

By the end of the second day after the election, the IEBC had transmitted over 96% of all results from polling stations. This was surprising (or was it) because during their pre-election simulation exercise, the IEBC did not convince observers that the system was capable of such a feat. However, the final few results would then take a while, nearly taking the whole gamut of the legally binding seven days within which presidential results should be declared.

11. The Moment When It Almost Went South

On 15 August 2022, six days after election results started streaming in, the final declaration was made, albeit amidst unprecedented drama. After stalling the entire day, the Commission chairperson Wafula Chebukati, dodging chaos and noise at the Bomas of Kenya auditorium, went on to defiantly declare the final presidential results. William Ruto had won.

Almost simultaneously, a presser called by four (out of the seven) IEBC Commissioners led by the Commission vice chairperson at the Serena Hotel was denouncing the presidential results being read by the Commission chairperson. The debacle would later become one of the issues to be determined by the Supreme Court, since it was part of the queries raised by petitioners, who objected to the legitimacy of the declared contested results.

There are many triggers that can provoke internal violence within a country. Such was that moment when the two factions of the Commission took different paths. That Kenya didn’t experience any embers can be attributed to many factors, key among them being that until that junction, the IEBC and the media had kept Kenyans abreast with results from different parts of the country, even as they trickled in. Restraint by politicians as well as quick action (shuttle diplomacy) by religious leaders also contributed to this.

12. Welcome to Purgatory, the Immediate Post-Election

And so, the immediate post-election period after result declaration was mainly characterized by the Supreme Court petition. The Observer noted that despite the constrained timelines (within 14), the Supreme Court bent backwards, to allow for complete filing of petitions and allow interested parties to engage in the process as amicus curiae.

An orderly framework for making the submissions was also agreed upon between the bench and the bar. The case was then prosecuted in public, with live media coverage. Debates in various fora, online and offline, provided for opportunities for further analysis of the issues being colourfully canvassed in the court by animated litigants for and against the petition(s).

As stated earlier, the verbal drama in the exchanges between different counsel is material for a book someday. On his part, the Observer was more interested in elements throughout these election processes which served to not only make Kenyans an informed citizenry, but also develop precedence and critical jurisprudence which shall shape the electoral reforms conversation moving forward. For instance, the court exposed the challenges within IEBC’s corporate governance, laying bare issues that will require quick remedies.

Ultimately, and even as the court made its decision – effectively retaining the status quo of the IEBC results declaration – Kenyans will almost always remain cognizant of the reality that the country’s presidential election results happen to split the country into two near-equal voting halves. Since the 2007 presidential elections, the difference in the final tallies of the two leading candidates has remained very minimal, forever tinkering with the possibility of a run-off. The importance of the country’s political unity, therefore, remains significant.

13. A Pat On The Back, And The Mandatory ‘Pull-Up-Your-Socks’

The Observer’s perspective, which can be supported by data and evidence from findings adduced from respective election reports, is that the bigger deduction out of the concluded electoral process is that despite some clear aberrations, Kenya’s conduct and management of its electoral affairs has improved tremendously since the return of multi-partism in 1992.

To the Observer’s mind, there will be major issues that Kenya must attend to, key among them being what model to use to establish a working and trusted Election Management Body. This is tied to the question of what ‘amount’ of technology is required to run the country’s elections. A lot of electoral reform conversations will be based on these aspects.

Moreover, there shall always remain a need to have positive engagement from all actors – the electorate, the political parties, the candidates, the IEBC, Parliament, the Treasury, the Police, the Judiciary, the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, the Political Parties Dispute Tribunal, the media, the church, et al – who working in concert, can enable the occurrence of successful elections. These, and the building of confidence and trust in the running of our public affairs, are where it’s at.

That said, it isn’t lost on the Observer that a lot of these are stories for another day.